Americans drink a lot of soda. In 2013, the average adult consumed 38 gallons of sugar-sweetened beverages annually–equal to eight cans a week. In the midst of a nationwide obesity epidemic, sugary beverage consumption continues to be a leading contributor to weight gain, type-2 diabetes, and heart disease.

Five year ago, Berkeley, California, became the first US city to tax sugar-sweetened beverages as it tried to change consumer behaviors. A study analyzing this policy found the tax reduced consumption by 52% between 2014 and 2017. Eight cities across the nation have followed Berkeley’s lead, including Chicago, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Seattle. Armed with this evidence, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Heart Association in March issued a joint statement formally endorsing the tax.

But even if taxes work, are they the only way to reduce the consumption of sweetened drinks? What’s the effect of printing warning labels directly on labels, as the United States has required for packs of cigarettes for over 50 years? Do labels influence behavior?

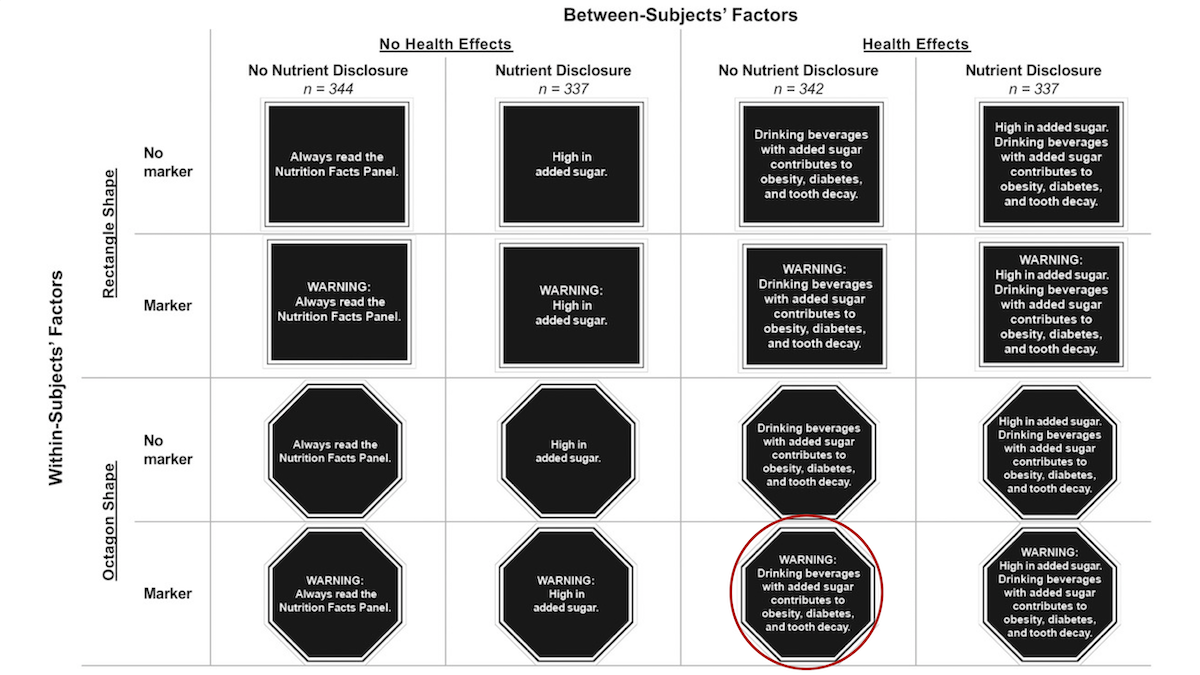

Photo via “How Should Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Health Warnings Be Designed? A Randomized Experiment.” Preventive Medicine, Academic Press, 14 Feb. 2019, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0091743519300490?via%3Dihub.

The team tested the effectiveness of 16 label designs, which differed in content and shape. Participants received one of four potential combinations of nutrient disclosure information and health effect description (the “between-subjects’ factors” at the top of the figure). Then, all 1413 participants received four potential options for label shape and use of the marker word “WARNING” (located on the left side of the figure).

Participants viewed labels directly on an unbranded bottle, as seen in the picture, and rated a format’s effectiveness in both discouraging sugary beverage consumption and raising awareness about negative health effects. The researchers suggest that the label circled in the figure above was particularly effective in evoking more thoughts of harm compared to others.

While sugar-sweetened beverage taxes have been effective, labelling may become more prevalent as an increasing number of states place moratoriums on new soda taxes.

Overall, labels that included health effects, nutrient listings, and were marked “WARNING” were perceived as more effective than labels without them. Octagonal labels were also found to be more effective than rectangular.

The researchers caution against adding too many words to labels. Longer labels, of course, are harder to read. “On balance, this is a ‘less is more’ situation,” said Anna Grummon, the lead researcher on the study. “It is likely better for policymakers to pick one or the other–describe health harms or use ‘High in added sugar’–but not to include both at the same time.”

And while sugar-sweetened beverage taxes have been effective, labelling may become more prevalent as an increasing number of states place moratoriums on new soda taxes. One of those states, California, enacted a ban until 2031, and a state senator proposed a bill to label bottles, cans, and boxes. Grummon suggests that more research will be necessary to demonstrate how taxing and labeling policies might work together to help consumers make healthier choices.

Image by Dennis Young from Pixabay