In the United States, almost 60% of hospitals are considered nonprofit organizations. Hospitals with this status are exempt from local, state, and federal taxes. In return, they are expected to provide benefits to the communities they serve. Much scrutiny has been applied to this quid-pro-quo relationship. The value of the tax exemptions (estimated to be $24.6 billion) coupled with the difficult task of measuring results of each hospital’s efforts continues to mire the subject in controversy.

Changes to the IRS code under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 were made to help bridge a disconnect between hospital officials and community members by improving transparency and accountability. One such provision requires nonprofit hospitals to perform and publicly publish a community health needs assessment (CHNA) and develop an implementation strategy to address community priorities every three years or face a $50,000 excise tax.

The core functions of public health include well-designed, data-driven, and collaborative community health assessments as a fundamental component in crafting appropriate and successful community interventions to address health issues. However, several key features differ between the public health model and medical model, which often guides hospitals’ approach, in both education and practice. Traditional medicine typically emphasizes treatment of patients, while public health incorporates preventive care that addresses broader social determinants of health for populations. Inclusion of these broader determinants as community benefits suggests nonprofit hospitals should intervene to address them in addition to providing charity clinical care.

Research findings to date

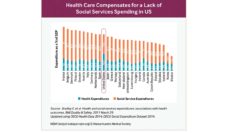

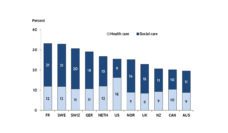

Hospitals’ community benefit activities have primarily focused on direct clinical care; very few activities or financial resources are dedicated to community-oriented programs. Furthermore, as demonstrated in a sample of Texas nonprofit hospitals, few hospitals developed CHNAs and implemented strategies that met public health quality criteria nor did the majority engage community members in meaningful participation throughout the assessment and planning process. While a more recent study found a number of urban nonprofit hospitals included language in their CHNAs reflecting an understanding of the causes of health inequity, few proposed effective strategies aimed at reducing the impact of broader social determinants of health.

Inclusion of these broader determinants as community benefits suggests nonprofit hospitals should intervene to address them in addition to providing charity clinical care.

Policy implications

Despite incremental changes over the past several decades, current legislation regarding community benefits and CHNAs does not provide hospitals adequate incentives or guidance to intervene and improve community health nor do they provide the teeth the IRS needs to enforce these mandates.

A population health outcomes-based measure is an ideal alternative to using monetary input alone to justify hospital tax exemptions. However, an outcomes-based approach comes with considerable complications. For one, the IRS requires interventions to have a direct link to health outcomes in order to be considered a community benefit which may understandably incentivize hospitals to maintain focus on direct care of their patients. Substantiating this relationship is a paradox well-known to public health practitioners: when population health interventions succeed, they often result in a lack of illness, creating the appearance of a lack of benefit. An additional and equally important matter is how hospitals define their communities. In the final IRS requirements, the definition of community for CHNAs was ultimately conceded to each individual hospital.

Thus far, the IRS has seemed hesitant to impose strict penalties on or revoke the tax-exempt status of hospitals. In fact, fewer than 1% of all nonprofit organization tax forms, not just nonprofit hospitals, were subject to audit in one review by the Government Accountability Office.

Substantiating this relationship is a paradox well-known to public health practitioners: when population health interventions succeed, they often result in a lack of illness, creating the appearance of a lack of benefit.

Recommendations

Some argue that shifting the focus of community benefit provision away from individual care to broader community needs places unfair burden on hospitals, whose expertise lies primarily in delivering acute care. While abandoning charity care for individuals is not a viable solution, neither is supplanting public health department operations. Instead, hospital resources could be used in partnership with local public health and nonprofit organizations to fill gaps in the provision of population health benefits, such as grants to address chronic conditions or personnel to aid with existing crises like opioid abuse.

Should the ACA be repealed, these provisions should be reintroduced separately or as provisions in whichever bill takes the ACA’s place. Regardless of the ACA’s future, the IRS requirements should be strengthened to include increased cross-sector collaboration and reporting of population health outcomes-based measures. Widespread health inequities and the resulting outcomes will continue to drive up the costs of care unless healthcare organizations, such as nonprofit hospitals, continue to make serious efforts to invest in long-term, population based strategies.

Feature image: CAMH Foundation, Intergenerational Wellness Centre Mosaic, used under CC BY 2.0