Ely, Minnesota is a two stoplight town with a population of 3,460. Nestled in the Vermilion Iron Range, Ely was once home to five bustling iron ore mines. Now, the local economy depends on adventure tourism. It serves as an outpost to the million-acre Boundary Waters Canoe Wilderness, one of the few places in the continental US where you can see the Northern Lights. Ely’s main drag sells canoe seats and wool long underwear, antler-shaped wine racks, and hand-carved cribbage boards.

In 2015, Ely’s 16 bed hospital closed its obstetric unit due to financial concerns. The birthing center in nearby Grand Marais closed the same year, leaving residents of northern Minnesota with longer and longer commutes to receive care. Ely residents were forced to drive an hour to the nearest obstetric unit. Grand Marais residents faced a two-hour drive. Those estimates assume perfect driving conditions, a pipe dream during Minnesota winters.

The hospital closure in Ely and resulting health care desert is a common story. Between 2004 and 2014, 179 rural counties in the US lost hospital-based obstetric services. Less than half of all rural counties have obstetric services, and the number shrinks each year. Hospitals cite legal and insurance costs and the challenges of recruiting physicians to isolated areas.

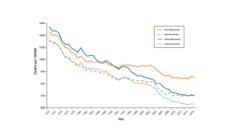

Losing obstetric services devastates rural communities. Katy Kozhimannil and team compared the birth outcomes in rural counties the year they lost services to the year before. In that short time span, babies were more likely to be born preterm. People are more likely to give birth in hospitals without a dedicated obstetric unit (often emergency scenarios) or someplace other than a hospital. Pregnant people in these communities receive less prenatal care and have fewer places to turn when things go wrong.

In most of the country, having a safe and healthy facility close to your home where you can deliver your baby is a given. Not so in Ely, Grand Marais, and many other small towns.

Obstetric closures wreak havoc on rural communities. Not knowing how many rural communities are affected by such closures causes counting and planning problems. According to many definitions of rural, the closure in Ely would not count as a rural obstetric unit closure, even though people who live in Ely overwhelmingly consider it a rural town. Ely is located in the same county as Duluth, Minnesota’s fourth largest city. If we identify rurality by county, Ely is considered urban, even though Duluth is over two hours away by car.

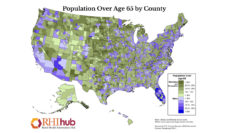

What it means to be rural is notoriously hard to define. Are there better ways to define rurality than by county? Census tract? ZIP code? Communities often span these administrative definitions. Most government definitions of rural start with a population limit. Everything above the limit is urban and then everything else is considered rural. But this ignores health care access realities. Suburbanites can access many services that people living in remote rural areas can’t.

Many times, the same area counts as rural for one federal program but not another. Rural Health Information Hub has even developed a tool called “Am I Rural?” that provides the status of a rural location, based on different federal rural definitions.

What can be done to curb rural obstetric closures? States can expand the services that nurses and midwives can provide without physician supervision. (States that have expanded scope of practice for nurses and midwives see fewer preterm births and fewer infant deaths than states that haven’t.) Medicaid, Medicare, and private insurers could increase reimbursement for rural hospitals especially for labor and delivery services. Federal policymakers could expand programs like the National Health Service Corps, which offers tuition reimbursement and training opportunities to rural providers. Finally, researchers and policy makers can interrogate the definitions they use of what makes something rural to ensure that all communities left without services can benefit from these programs and policies.

In most of the country, having a safe and healthy facility close to your home where you can deliver your baby is a given. Not so in Ely, Grand Marais, and many other small towns.

Young families are leaving the red pines and black spruces of these towns for the suburbs where they can more easily access the healthcare they need. This change is not inevitable. But to prevent and reverse it, we need to take a hard look at what counts as rural and how to support low-resource rural hospitals.

Photo via Getty Images