Why don’t public health organizations use the techniques of marketing to combat the epidemic of obesity? That’s a question that colleagues and I tested in Appalachia, with encouraging results.

Marketing is at the heart of the obesity epidemic. The sharp rise in obesity since the late 1970’s has been accompanied by a shift to hyper-processed foods and beverages, from pizza to sugary drinks. That junk food consumption didn’t just happen. Corporations selling those products paid for it with billions in advertising, promotions, enticing packaging, favorable pricing, and retail slotting fees. The billions that Americans spend on junk food is hard evidence that all this works. And if marketing can sell pizza and soda, why can’t it sell apples and broccoli? More important, why can’t marketing un-sell pizza and soda? It was that last question that we tried to answer.

This isn’t a new idea. Paid counter-advertising has long been standard practice in smoking prevention. Testimonials from disease sufferers un-sell smoking by making smoking-caused diseases vivid and undeniable, forcing smokers to confront the consequences of their habits. But public health programs combatting obesity have mostly avoided paid counter-advertising. This reluctance probably stems from a combination of fear of industry and political pushback, difficulty scrounging money for media placement, a historic faith in face-to-face interactions, and a limited base of evidence on the effectiveness of counter-advertising for eating behavior. We hoped our project would help develop that evidence.

Because focus group participants saw cigarettes as particularly unhealthy, putting the two products in the same frame prompted them to rethink their drink habits.

The campaign took place in the Tri-Cities region of northeast Tennessee, southwest Virginia, and southeast Kentucky, a rural area with a population of 780,000. Formative research there showed that young adults drank sugary drinks heavily despite knowing the connection to obesity and diabetes; they just discounted those risks. The campaign messages, developed with community leaders, compared the health effects of sugary drinks to those of cigarettes, highlighting heart disease, cancer, and tooth loss. The videos were simple: a regular guy talking to viewers while holding a bottle of soda in one hand and a pack of cigarettes in another. Because focus group participants saw cigarettes as particularly unhealthy, putting the two products in the same frame prompted them to rethink their drink habits.

We ran the campaign for 16 weeks on television and digital channels (YouTube, Hulu, and Facebook). To reinforce it, we asked local businesses, hospitals and nonprofit organizations to promote water in place of sugary drinks with their employees and customers, using the campaign tagline Live Sugarfreed. Distributing the ads, including the local organizing, cost under $300,000, or less than 40 cents per capita.

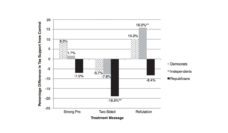

We evaluated the campaign using data on beverage sales from retail stores before and after the campaign, in both the intervention area and a matched comparison area in rural Virginia, supplemented with phone surveys to assess the campaign’s reach and changes in people’s attitudes.

Half of people surveyed remembered seeing campaign ads, and of those who did, nearly two-thirds called the ads “important.” Sales of sugary drinks, including soda, fruit drinks, and sports drinks, fell 2.0% in the intervention area but rose 0.9% in the comparison area; in a multivariate model the relative decline in sales of sugary drinks was 3.4%. That decline was driven almost entirely by a 4.1% relative drop in sales of soda, which the ads highlighted. The survey data generally backed this up, with people who saw the ads more likely to view sugary drinks as a cause of cancer and heart disease. Oddly, the surveys showed an increase in the percent of people saying they consumed sugary drinks in the past week, a subjective measure that didn’t match the objective sales data.

These results weren’t perfect, and the effect of the intervention wasn’t large. Still, we were encouraged that such a short campaign had any measurable effect on sales, and the 3.4% relative sales decline wasn’t far from the 6% fall in sales after the soda tax was enacted in Mexico. Campaigns like this should be tested on a larger scale and for longer. Maybe the messages should be harder-hitting, falling back on smoking prevention’s tried-and-true testimonials. And maybe we’ll ultimately learn that the best approach to un-selling sugary drinks is the same combination we used for tobacco: taxes and paid media.

More generally, this experience says that those of us in public health should try the techniques of marketing more. We are not the only ones in the behavior-change business. Companies that sell unhealthy products, from cigarettes to chips, have decades of experience shaping consumer behavior. They have learned what works. If marketing can entice people to drink more soda, it ought to be able to do the opposite. We merely have to find the right messages, learn the best ways to deliver them, and define the dose-response curve. With the obesity epidemic costing this country over $100 billion a year for health care alone, developing our methods of counter-marketing is well worth it.

Feature image: still from #LiveSugarfreed