A teenage girl sits on the examination table in her doctor’s office. She stares at her hands and mumbles, “And… is it safe to… um…” The doctor’s face dons a comforting smile. “Have sex? There’s no reason you can’t! I inserted it into your uterus, okay? You should be fine, do everything as usual…but you need to condomize, okay? Protect yourself against HIV and STDs.”

It’s Season 5, Episode 4 of the MTV Staying Alive campaign-turned-TV-drama, Shuga. One of the main characters, Bongi, has just become sexually active and, at the urging of her aunt who is a nurse, she’s getting her first intrauterine device (IUD). As the doctor answers Bongi’s questions, she simultaneously and intentionally teaches the millions of viewers not just in South Africa, but throughout the continent and around the world.

In this most recent season alone, the characters confront issues like abuse, manipulation, teenage pregnancy, questioning sexual identity, and safe sex. Relatable characters and a compelling storyline drive the entertainment value of good health education. This is the inspiration behind Shuga’s mission.

“The fact of the matter is, if it’s not entertaining to begin with, no one’s going to watch it,” says Georgia Arnold, Senior Vice President of Social Responsibility at Viacom International Media Network and Executive Director of MTV’s Staying Alive Foundation. To a forum of public health researchers and students at Boston University, Arnold explained, “That’s actually what we set out to do is to produce really good content that everyone wants to watch, that we happen to weave messaging into.”

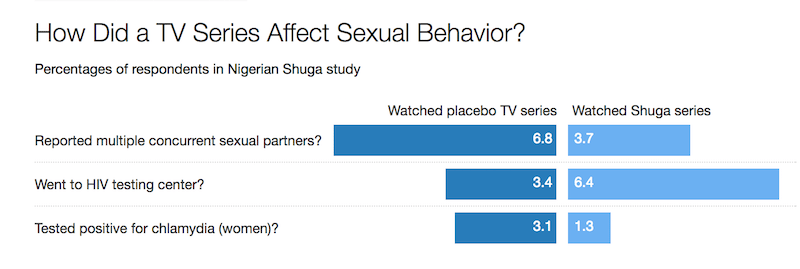

In this case, success is defined by sexual health behavior change, and preliminary results from a collaborative World Bank study in Nigeria show that MTV Shuga is making a mark. Researchers found that certain measures regarding sexual health behaviors and attitudes improved for the participants who watched the show’s third season, highlighted in the graphic above. Among viewers of the show, prevalence of chlamydia dropped by 58%, reporting of multiple partners dropped by 15%, and participants were 35% more likely to report getting tested for HIV during the 6-month study period compared to a placebo group that viewed a movie of similar sexual content and length but without the intentional messaging. They were also 35% less likely to consider HIV a punishment for sleeping around.

Some behaviors showed less promising results, such as condom usage and perception of domestic violence. However, the show continually works to improve, remain relevant, and evaluate its impact. For the most recent season, the show is using an evaluation technique called social media listening. The study team follows 20 phrases or words on Twitter across a period of 6 months “to see how that conversation changes with the screening of MTV Shuga,” according to Arnold.

She says that their impact can be attributed to three main strengths: the use of the MTV brand, their commitment to reflecting young lives, and direct collaboration with young people in the production process.

“The fact of the matter is, if it’s not entertaining to begin with, no one’s going to watch it,” —Georgia Arnold

“We do panels before we start story arching, where we sit there and we ask young people from a township that is very similar to the one that we filmed in just outside of Johannesburg, what their stories are,” she explains. “And then we took all of the stories they told us and turned it into the story arcs and eventually the scripts for this series.” The panel also lets the producers know what works and what does not. One member of their viewer panel voiced approval of a storyline in which a character let her teacher know she was pregnant by him — the panelists’ best friend had the very same experience weeks before.

Many evaluations have been conducted to detect the role of the media and edutainment in inciting behavior change. Researchers in communications have applied theory and detected consistencies in “attitudinal impact” within ‘edutainment.’ Other television series and movies like East Los High and Contagion show signs of success. But Arnold acknowledged the relatively singular success of MTV Shuga. “That worries me,” Arnold shared. “I don’t want to be unique in what we do.”

Why might this kind of media-based behavior change program have such a limited range of impact?

“My experience is that people in the industry hate the term ‘edutainment,’” suggested Alex Horowitz, filmmaker of the documentary Hamilton’s America, during the same forum at Boston University.

“Yes we do!” Arnold agreed.

“I like to think… that the best entertainment can educate. And the best teachers we ever had were entertainers in a way, right? Edutainment has always existed. Call it what you will. It’s just, if you seek out to make ‘edutainment,’” Horowitz said with a simultaneous Popeye-like arm motion, “I’m… I’m skeptical of you.”

Of his own documentary he said, “The fact that it’s educational is just the wonderful byproduct.”

Feature image: Still from MTV Shuga, Season Five, Episode 4, Segment 2 © 2017 Staying Alive Foundation Inc.

Chart from www.worldbank.org