Around noon on a Thursday in June, Amanda Phillips died riding her bike in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Phillips was 27, a barista and nursing student. She was passing through Inman Square, one of the busiest intersections in Cambridge, when the driver of a parked car unexpectedly opened the car door into her path. Unable to swerve, she struck the door and was knocked off her bike just as a landscaping truck was passing. She was pulled under the wheels and killed.

It’s impossible to say exactly what it would have taken to prevent Phillips’ death, or any of the thousands similar accidents that take place in cities all over the U.S. every year. However, poorly designed roads may play a large role in causing these crashes. One possible a solution is “Complete Streets,” a transportation policy and design approach that seeks to promote infrastructure that keeps all road users in minds, rather than just automobiles.

…a complete street is a road that is designed to accommodate pedestrians, bicycles, cars, and public transportation safely and efficiently.

According to the National Complete Streets Coalition, a complete street is a road that is designed to accommodate pedestrians, bicycles, cars, and public transportation safely and efficiently . There is no one model for a complete street, but they can include various combinations of sidewalks, bike lanes, protected bike paths, special bus lanes, safe crossing opportunities for pedestrians, speed bumps, and narrower travel lanes for cars.

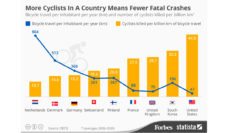

Of the 29,989 people killed in automobile accidents in America in 2014, 4,884 were pedestrians and 726 were cyclists. Studies have shown that even small improvements in road safety conditions can have large impacts on these numbers. According to a paper by Connor Reynolds and colleagues published in Environmental Health Perspectives, simple painted on-street bike lanes can decrease collisions with cars by up to 50%. A Federal Highway Administration pilot program cited in an American Public Health Association report showed new infrastructure and education programs encouraging active transportation in four major U.S. cities created a $6.8 million reduction in mortality-related costs due to both improved health from increased usage and reduced injuries from accidents.

However, all bike lanes are not created equal . While painted, on-street bike lanes have a well-documented effect of reducing collisions, they still leave riders vulnerable to inattentive drivers who might drift into the lane. Additionally, if these lanes are on streets with parking, they often leave cyclists in the “door zone,” where they might be struck by drivers and passengers exiting their cars. Even in the absence of on-street parking, cars may often stop or park illegally in the bike lane, forcing cyclists back into traffic.

A study published in 2009 by Kay Teschke and others at the University of British Columbia in 2009 tested the effectiveness of these options by tracking the number of injuries along selected routes in the cities of Toronto, Ontario and Vancouver, British Columbia. They found, unsurprisingly, that protected bike lanes, or “cycle tracks,” which use physical barriers like curbs or medians to separate cyclists from traffic, were by far the safest, leading to one-tenth the rate of injuries compared to similar roads with no cycling infrastructure. On-street bike lanes on streets without parked cars were found to produce about half as many injuries. Shared spaces, like shared road lanes and pedestrian paths, were found to produce no statistically significant reduction in injuries.

Beyond increased safety, there is evidence that complete streets lead directly to increases in walking and bicycling for transportation in local populations.

Each community faces its own challenges when attempting to update their infrastructure to accommodate bicycle and pedestrian traffic. Big cities must balance efforts to create safe spaces for vulnerable users with concerns about increased congestion on already crowded roadways that have little room for expansion. Rural roads often feature higher speed limits, more truck and large vehicle traffic, winding curves, lack of sidewalks, and inconsistently sized shoulders.

Beyond increased safety, there is evidence that complete streets lead directly to increases in walking and bicycling for transportation in local populations. Cycling, walking, and other forms of human-powered transportation can create significant health benefits in a nation with an ongoing obesity crisis.

Cambridge is an example of a city working to find the right balance. Like many communities in the Northeast, it’s an old city with narrow streets, many of which were laid out before the invention of the automobile. It is also home to a significant population of cyclists, with up to 9% of residents commuting to work by bicycle, more than double the 4% national average.

Inman Square, with its diagonal five-way intersection, on-street parking, tightly packed business and residential apartments, heavy pedestrian traffic, and several crosswalks, was already one of the city’s main targets for a Complete Streets overhaul before Amanda Phillips’ death. Soon after the accident, the city moved to fast track plans to improve safety in the square and surrounding roadways. Six months later, Inman Square has seen only modest changes. Two bike lanes, painted brightly green to draw the attention of passing drivers, have emerged on the street where Phillips was struck. Also, chained to a lamppost on the side of the road, is a stripped-down, white-painted bicycle, a “ghost bike”, left as a memorial by the local cycling community to the life that was lost but which may yet become the inspiration for dramatic safety improvement in this congested city.

Feature image: Nick Gray, Bike Safety Check, used under CC BY-SA 2.0 license