Death certificates are more than a bureaucratic record that collects dust. They are a trove of data that inform public health research, policymaking, and resource allocation. For instance, the current tracking of and planning to address the opioid crisis in Massachusetts relies heavily on information from death records. Based on how widely they are used, it seems logical to assume death certificates are accurate.

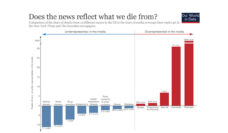

I learned otherwise in an epidemiology class. One of my classmates, a physician, challenged the legitimacy of death certificate data and offered a compelling explanation of the inaccuracies. I decided to dig further. For public health, demographic data is a core resource for understanding patterns of morbidity and mortality. If an information source is not trustworthy, in what ways do the inaccuracies affect health policy and programming? Can death certificates be trusted to inform research and the implementation of programs that aim to save lives? I set out to investigate this public health mystery by making a documentary film.

I chose documentary because I wanted to explore the veracity of death certificates in a narrative context. With open source equipment, I made a 10-minute film. Three respected experts graciously offered their knowledge to shape the narrative: Dr. Tom Land, a public health data scientist; Dr. Al DeMaria, an infectious disease epidemiologist; and Dr. Michael Grodin, a health law ethicist. Each helped me build the storyline by speaking from their decades of experience.

Today public health professionals are unveiling innovations in the way death certificates inform prevention efforts.

The story begins in the Massachusetts State House. In 1849, the American Statistical Association successfully petitioned the Massachusetts State Legislature to legally grant the use of death records for tracking preventable and premature deaths. Following this legislative turning point, other states adopted similar laws that would also lead to a movement to establish public health departments. Tracking mortality is now a ubiquitous practice across the country. Today public health professionals are unveiling innovations in the way death certificates inform prevention efforts.

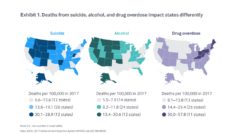

Public health professionals often link death certificates with other government records to solve public health mysteries. Dr. Land described how the Massachusetts Department of Public Health employs this approach to track the current opioid epidemic: “We link together information from the Medical Examiner, the State Police, and death certificates to create a model that predicts the likelihood a death is opioid related.” Information collected across various government agencies can intertwine to tell the complete mortality story of an individual.

Physicians are a vital character in the death certificate narrative and their training or lack of training influences accuracy. Other than coroners, they are the primary authors of death certificates. A lack of physician training on recording mortality data emerged during my interviews and research as a key factor that can lead to inaccuracy. Dr. DeMaria and Dr. Grodin, who are also clinicians, explained that junior medical staff with inadequate training are traditionally tasked with death certificate data entry in hospitals. Training medical students to correct data entry and emphasizing the public health value of death certificates will be an important step toward improving accuracy.

Parallel themes build the death certificate story. The design of a strong data collection system and robust training for those recording data are critical to ensuring that mortality data is accurate. Moving forward, accuracy of data is not the only important consideration. Institutions, public and private alike, influence the structuring of data systems. I now work as a legislative aide at the Massachusetts State House. From observing the intersection of advocacy, policymaking, and community engagement firsthand, it has become clear to me that institutions are a key influencer in the use of data to improve health outcomes. History shows us that saving lives begins with keeping track of and scrutinizing how we die.

Feature image: Alexander Lyubavin, IMG_2991 гроб, used under CC BY 2.0