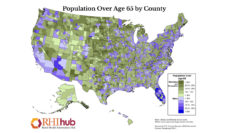

Alzheimer’s disease is the sixth leading cause of death in the United States and the only leading cause of death with no known treatment or cure. A third of people in the US aged 85 and older have Alzheimer’s disease, but that burden does not fall equally across the population.

Latinxs and blacks have approximately two to three times higher risk of dementia than whites. Two-thirds of those with an Alzheimer’s diagnosis are women. Those who are higher-educated have much lower risk of dementia. Reasons for these social disparities in risk are likely complex and require more research. We also do not yet have a good understanding of how different groups bear the burden of cognitive impairment beyond risk.

We, therefore, study different aspects of the burden of cognitive impairment among black, Latinx, and white women and men at different levels of education. We used the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), which is a study of residents aged 50 and older and their spouses in the US. The HRS surveys the same people every other year, collecting information on health and cognitive functioning. We analyze cognitive function scores for 29,304 respondents over the period 1998-2014 to calculate three important dimensions of the burden of impairment: what fraction of the population ever experiences cognitive impairment, at what age individuals first experience impairment, and for how many years they live impaired.

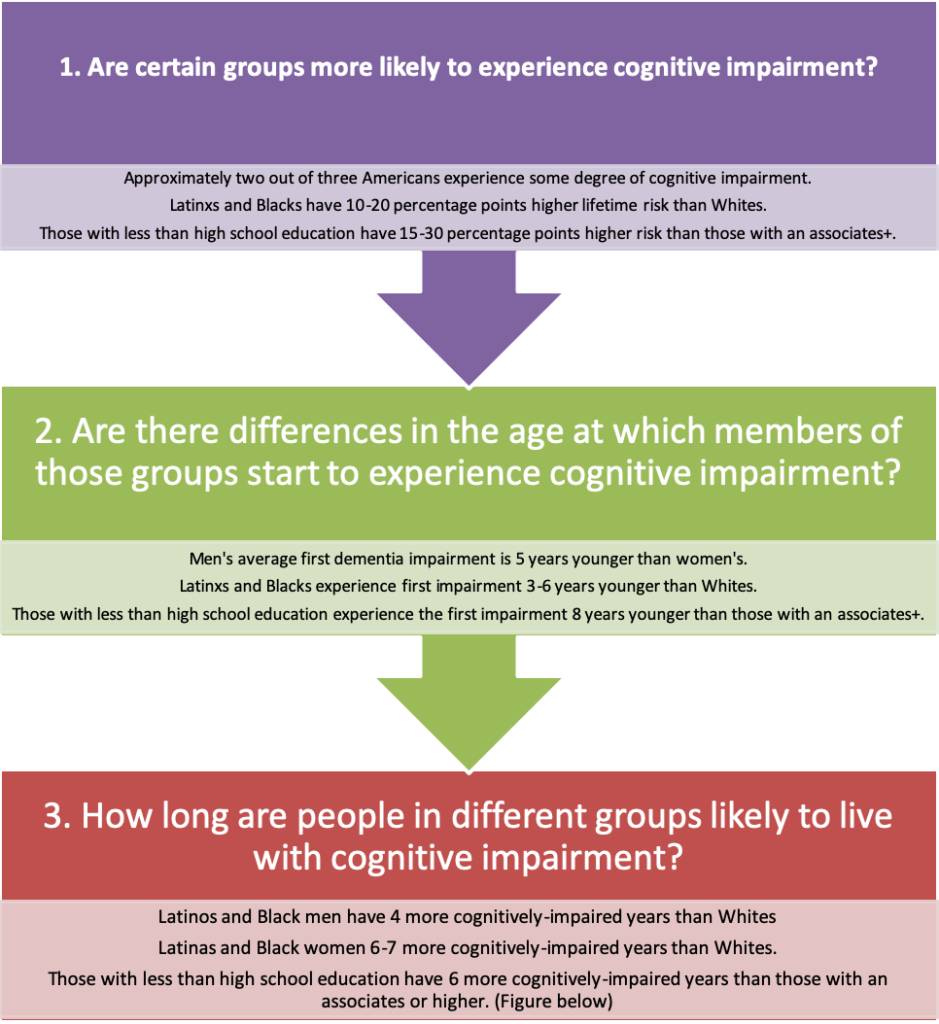

In the below table, we present our three primary questions and some key findings:

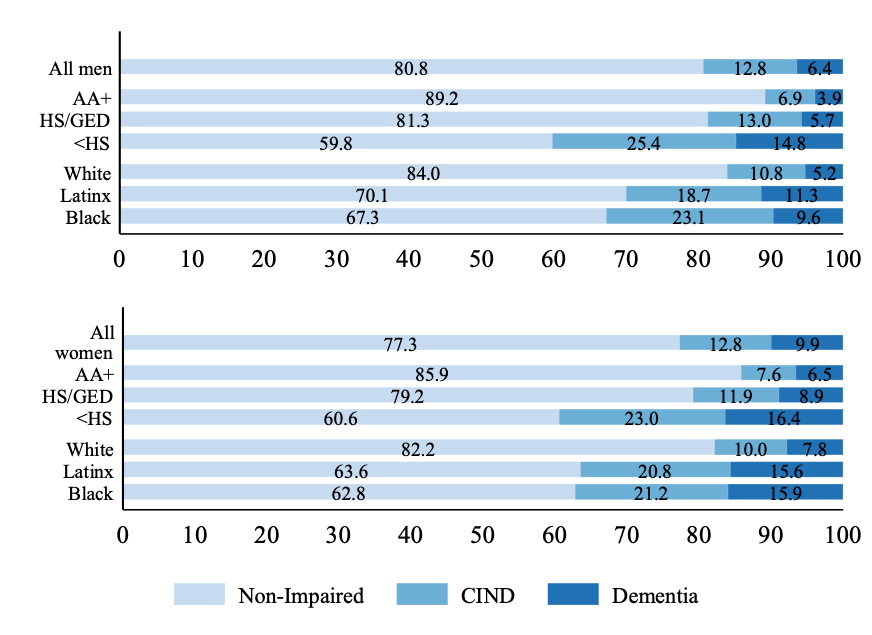

The figure below illustrates cognitive health expectancies by gender, race/ethnicity, and educational attainment, where pale blue indicates percentage of life expectancy after age 50 not cognitively impaired, medium blue indicates cognitive impairment-no dementia (mild impairment), and darker blue indicates dementia. The length of each bar represents 100% of a group’s life expectancy starting at age 50.

Racial/ethnic and educational disparities are stark. For example, men with an associates degree or higher can expect to be in good cognitive health about 89% of their years from age 50 until they die, compared with those with less than high school’s 60%. Black women can expect to spend about 21% of their lives from age 50 to death with mild impairment, compared with white women’s 10%. Black men and Latinxs spend about 10% of their lives between age 50 and when they die severely impaired, compared with white men’s 5%.

Racial/ethnic and educational disparities are stark. For example, men with an associates degree or higher can expect to be in good cognitive health about 89% of their years from age 50 until they die, compared with those with less than high school’s 60%. Black women can expect to spend about 21% of their lives from age 50 to death with mild impairment, compared with white women’s 10%. Black men and Latinxs spend about 10% of their lives between age 50 and when they die severely impaired, compared with white men’s 5%.

Looking at these three sets of numbers together (risk, age, and time impaired), it is clear that for the most advantaged groups (white and/or higher educated), cognitive impairment is both delayed and compressed toward the very end of life. In contrast, despite the shorter lives of disadvantaged groups (black and/or lower educated), they experience a higher lifetime risk, a younger age of onset, and more years cognitively impaired.

The groups who face greater risk and longer expectancies in cognitive impairment – blacks, Latinxs, and those who have less education – are also those likely to have the fewest economic resources and the least access to quality healthcare.

What does it all mean?

These racial/ethnic, gender, and educational disparities have important implications for the burden of cognitive impairment. The groups who face greater risk and longer expectancies in cognitive impairment – blacks, Latinxs, and those who have less education – are also those likely to have the fewest economic resources and the least access to quality healthcare. Regarding gender disparities, women appear to bear the greater burden both in terms of likelihood of providing care for male partners (as men have a younger mean age at onset) and in that women have higher lifetime risk and longer impairment. Furthermore, women’s longer life expectancies compared with men means they often face that increased risk whilst living alone, and may require more years of social support. While racial/ethnic disparities are partially explained by education, other inequalities in stressors and health factors are also likely causal. To better inform policy measures, further research is required to identify the mechanisms driving these disparities in cognitive impairment.

Photo via Getty Images