Over the past year, an increasing number of novel therapies and technologies hit the market for a host of chronic medical conditions from cancer to diabetes. With these treatments came a renewed focus by the health system, the public, and the technology sector on the use of precision medicine, or personalized, highly-specific treatment, for disease management. While this has led to an exciting time in health care, we need to proceed with caution as these advances may widen racial health disparities in the United States.

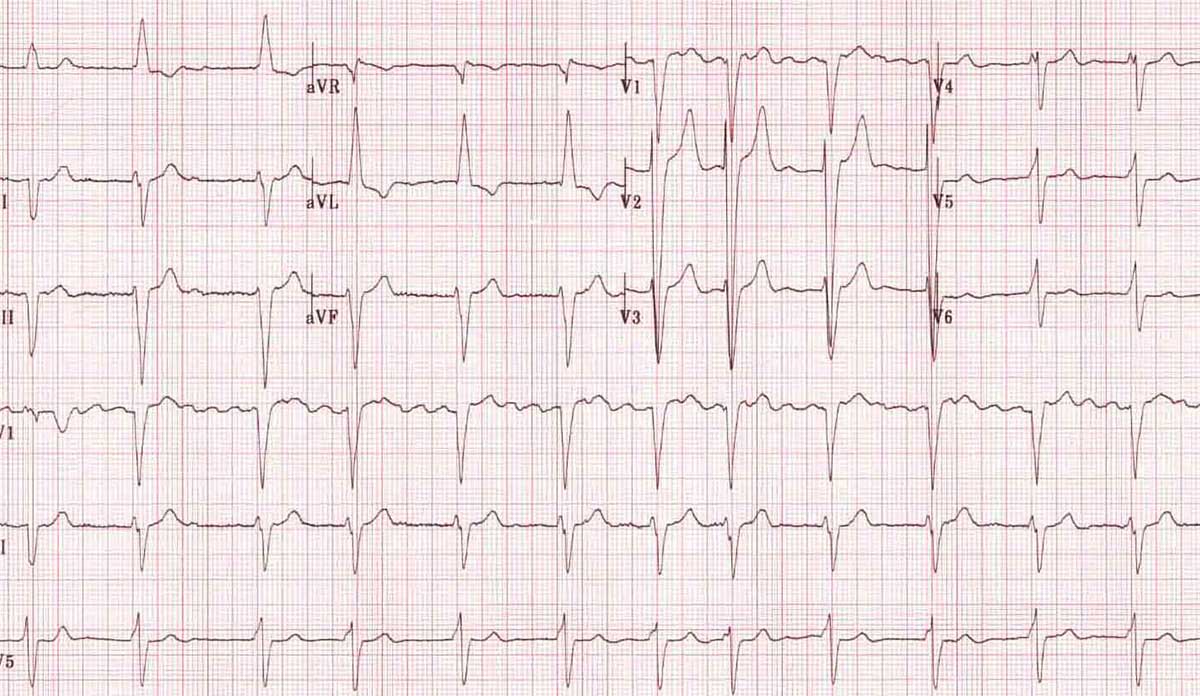

As a primary care physician who provides the initial assessment and management for several chronic conditions, I am always pondering this question. My colleagues and I recently set out to investigate racial disparities in disease management on a national scale, focusing on a condition known as atrial fibrillation (AFib), or an irregular heart rhythm.

AFib raises an individual’s risk of stroke and death and is increasingly common in the US given our aging population. Research shows that Black patients with AFib have a higher risk of stroke and death than White patients, resulting from several factors connected to socioeconomic status and access to health care. We hypothesized that another possible reason for higher complication rates in Black patients with AFib is differential treatment of the condition, specifically treatment with a newer class of stroke-preventing blood thinners, called direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs).

Our findings also show that socioeconomic status alone is not enough to explain the differential treatment by race we see in the use of novel treatments.

Our findings, recently published in JAMA Cardiology, were striking. We found that, among patients with AFib, Black individuals had a 25% lower likelihood of receiving any blood thinners. When they were prescribed blood thinners, they had a 37% lower likelihood of receiving the newer class of DOAC medications compared to White patients. These differences held true even for Black patients with health insurance, high incomes, and high levels of education.

What do our findings mean for racial disparities in the use of novel treatments? For starters, health disparities still exist despite decades of research, quality improvement, and policies intended to reduce them. Our findings also show that socioeconomic status alone is not enough to explain the differential treatment by race we see in the use of novel treatments.

Possible mechanisms that remain unexplored include patient-level factors such as trust in the health system and health literacy on decisions around novel medications. At the provider level we need to examine the role implicit bias might play when initiating conversations about novel treatments with minority patients. Lastly, at the health system level, more research needs to be done on the implications of high costs of novel treatments, across the socioeconomic spectrum.

Whether we like it or not, society is moving towards an age of precision medicine, and the desire by patients, and providers, to be treated and to treat with the latest, most advanced therapies is a valid one. How prepared we are as a health care system to address these desires and to ensure equity remains to be seen. We hope the findings of this study serve as a reminder to take a pause when a new therapy comes out and ask: who is most likely to benefit from this treatment and how can we ensure that it is distributed fairly?

Feature image: Popfossa, AF, LAD, LBBB, used under CC BY-NC 2.0