Public education is widely seen as a public good – our society’s investment into future generations, where all children have a shot at achieving their full potential. We know education matters and has vast potential to shape a child’s future from job earnings to life expectancy.

In reality, a child’s potential for life success is shaped before ever setting foot in a classroom. Scientists, educators, and health care providers have come to understand that experiences in early life can shape the architecture of the developing brain. In 1998, a landmark study showed that adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), such as witnessing abuse in the home, were connected with having 9 of the 10 leading causes of adult death. Over the last 3 decades, the spotlight on ACEs has steadily grown, not only within the biomedical community but among educators, journalists, and politicians.

Focusing on ACEs, while essential, may only be half of the solution. In our recent study, we examined five years of National Survey of Children’s Health data. Gathering perspectives from remote homes in Alaska to crowded apartments in New York, this survey allowed us to understand another vital dimension of young children’s lives. Positive early childhood experiences (PECEs) capture various experiences known to cultivate healthy development for children. Specifically, we set our sights on safe and stable environments (such as how safe families feel in their neighborhood); nurturing relationships (such as whether families talk together about their problems); home learning opportunities (such as how often children are read to); and family routines (such as whether children have consistent bedtimes).

We place our hopes – and votes – into policies that may someday limit these traumas from happening, such as expanding financial supports for families.

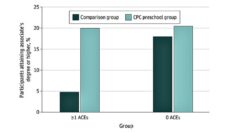

While the patterns we saw were perhaps unsurprising, they were striking. Children in households with greater positive experiences were more often ready for school – they could self-regulate, and had the learning, emotional, and physical skills needed for success in the classroom. The positive experiences seemed to support school readiness even when considering children’s experiences with adversity. To illustrate, kids with high levels of PECEs but no history of ACEs had more than a 4 times higher chance for being school-ready compared to kids with low PECEs. Similarly, children with high PECEs and multiple ACEs (for example, a child in a home with a father in jail and a mother with a substance use disorder) also had a greater than 4 times higher likelihood of being ready for school.

Notably, having greater positive experiences correlated with school readiness irrespective of children’s racial/ethnic or income background. This was an important finding given known inequalities in school readiness for minority children and those living in poverty. Therefore, despite how common and harmful ACEs can be for child well-being, the study illustrates the remarkable resilience of young children and the role that PECEs can play in setting them up for success.

As a primary care doctor and a public health researcher, we have seen firsthand how many parents are trying their best to support their kids’ health. But for many families, the cards are simply stacked against them. Typical clinical interventions, like inhalers and counseling referrals, seem like band-aid solutions over much deeper-rooted problems of mass incarceration, addiction, and community violence. We place our hopes – and votes – into policies that may someday limit these traumas from happening, such as expanding financial supports for families.

In the meantime, PECEs provide an opportunity for child well-being stakeholders to band together today. Filling our homes, classrooms, doctor’s offices, and communities with opportunities for children to have positive experiences can help ensure kids – even those in the toughest circumstances – have the tools to thrive for years to come.

Photo via Getty Images