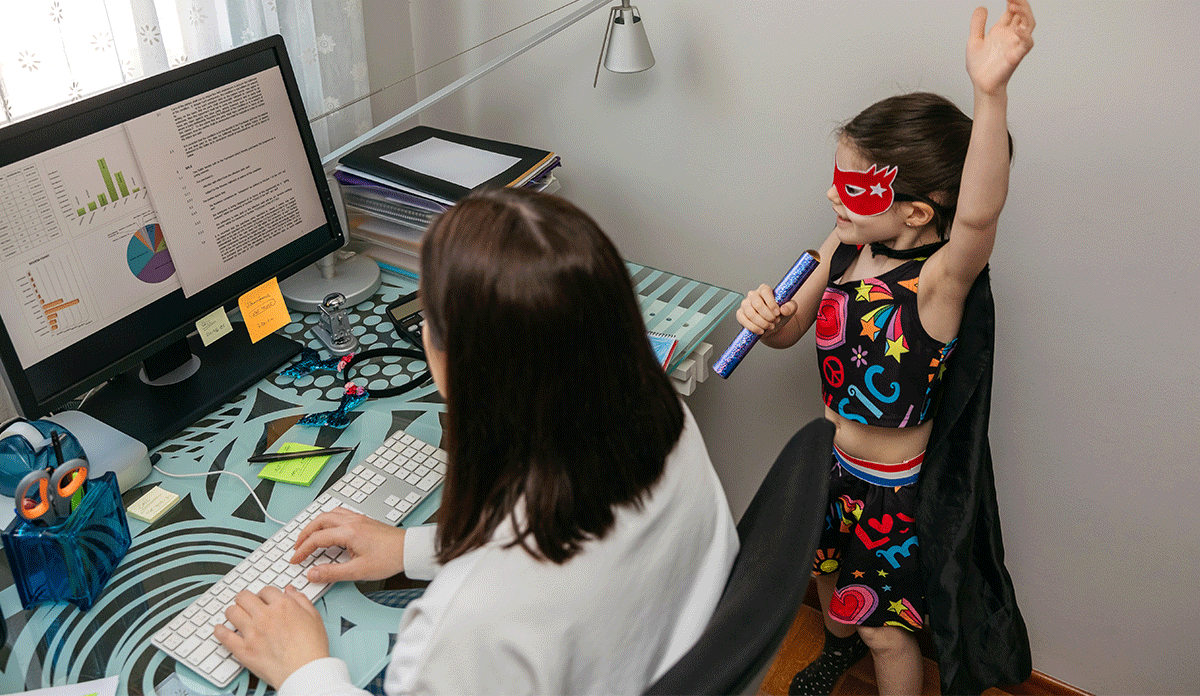

The pandemic turned bedrooms into offices, kitchens into classrooms, and parents into teachers. Following Covid-19 school closures, 483 million children worldwide switched to online school. In the pandemic year, parents have juggled the responsibility of educating their children with their professional lives. Many have made difficult decisions to quit working in the absence of other childcare options. The cumulative weight of these obligations has compromised parents’ mental health during the pandemic.

In April 2020, 3 million Americans filed for unemployment benefits, a population that included many parents. In an analysis published in The New York Times, Ernie Tedeschi found that 700,000 mothers of school-aged children, along with 150,000 fathers, left their jobs between February and September 2020.

The pandemic caused schools and day care programs to close, meaning that parents lost childcare. With schools closed, families lost access to free or reduced cost school. This forced some parents to quit their jobs in order to take care of their families, if they hadn’t lost their job already. On top of losing income, without a job, many families lost employer-based health insurance.

To better understand what parents went through during this time, Shawna J. Lee and colleagues administered a nationwide online survey to parents with children age 12 and under in April 2020, five weeks after the World Health Organization named Covid-19 a pandemic. Sixty-nine percent of respondents were mothers, 31% were fathers, and 1 in 4 had sustained employment changes. At that time, 78% of parents were helping children with online school: making sure their children attended zoom classes, helping them with lessons, and monitoring homework. They were doing this on top of all their other parental, family, and professional responsibilities. Little surprise that 40% of parents reported being depressed.

Parental stress was positively correlated with high child anxiety scores, suggesting that the wellbeing of parents translated to the wellbeing of their children.

Parental stress was positively correlated with high child anxiety scores, suggesting that the wellbeing of parents translated to the wellbeing of their children. Parents noticed that their children began to act differently with the onset of social distancing measures, with 35% reporting that their child had become sad, depressed, or lonely.

But social isolation from outsiders also brought many families together. Parents reported giving their child more hugs, telling more bedtime stories, and having more playtime with their children. Since positive parent-child interactions are associated with better mental health outcomes, some home lives may have discovered new comforts.

The pandemic started over a year ago, but will impact mental health today. Massachusetts recently passed legislation that requires medical insurance to reimburse for mental health services via tele-visits as well as in-person services. At the same time, mental health specialists are becoming more integrated as a part of primary and pediatric care. Dr. Archana Basu and Dr. Karestan Koenen believe that the pandemic’s impact on parent and child mental health largely depends on the severity of losses – food security, housing instability, and deaths of loved ones.

Dr. Basu and Dr. Koenen speculate that a majority of parents and children are unlikely to acquire long-term mental health disorders. However, they note that the pandemic will forever impact how we respond to trauma, and how that trauma affects our trust in institutions—schools, workplaces—that too often collapsed during our Covid-19 moment.

Photo via Getty Images