Let’s start with the good news. The population of individuals who are incarcerated in federal or state prisons in the United States is slowly but steadily shrinking. The rate of imprisonment in the US is the lowest that it has been since the late 1990s. According to Bureau of Justice Statistics, our nation’s prison population dropped to just under 1.5 million for the first time in more than a decade. The credit for this auspicious news goes to prison reform measures designed to alleviate overcrowding and reduce expense.

Now the bad. The US continues to lead the world in the rate at which it imprisons its citizens (as well as its non-citizens), and this country has a long way to go to relinquish this first place position to its closest contender, Russia. A decline in imprisonment has not been uniformly noted across the US and the prison population has actually increased in 20 states nationwide. Furthermore, racially based sentencing and gross human rights violations have continued to lead to blatant disparities in who gets incarcerated. The imprisonment rate for Black females is twice that of White women. For Black males, the rate is six times higher.

The bad news gets worse. Prison reform and the subsequent increase in prison release may have collateral consequences on the health of communities. The prevalence of HIV infection among the incarcerated is four to five times higher than among the non-incarcerated, largely due to high risk behaviors such as injection drug use and transactional sex prior to incarceration. Not all correctional facilities have implemented comprehensive HIV testing, prevention, and treatment services for inmates. Substance use and mental health treatment are often non-existent for many living behind bars. Individuals who are discharged from prison and living with HIV are often not linked to care and vital treatment. Without treatment, the risk of adverse health outcomes and HIV transmission to others post-release may be heightened.

My colleagues and I conducted a study to determine if there is an association between the rate of prison release into specific communities (defined by ZIP codes) and new HIV diagnoses in those communities. We looked at cities in the South where more than 50% of Black individuals in the US live and where the rate of HIV infections is highest. Previous studies have described how well individuals living with HIV who have been incarcerated fare post-release. We wanted to know if the impact of prison release on health extends beyond the individual to the community.

This study found that, if 10 additional individuals were released from prison per year, there would be a 4% increase in overall five-year HIV diagnosis rate or more than nine additional people who acquire HIV infection per 100,000 population per year.

We obtained ZIP code linked data from nine southern cities on prison release rates from the Justice Mapping Center and five-year cumulative overall, male and female HIV diagnoses per 100,000 population per ZIP code from AIDSVU, an interactive online mapping tool that visualizes the impact of the HIV epidemic on communities across the United States. We then created statistical models to determine associations between ZIP code-level prison release rates and HIV diagnoses rates. This study found that, if 10 additional individuals were released from prison per year, there would be a 4% increase in overall five-year HIV diagnosis rate or more than nine additional people who acquire HIV infection per 100,000 population per year.

What do these results tell us and how do they inform policy? First and foremost these results do not suggest that efforts to decrease the number of people in US prisons should stagnate. Instead, these findings highlight the urgent need for comprehensive reform to improve health care in prisons and jails. Such improvements must increase HIV testing, prevention, care, and treatment services as well as mental health and substance use services.

At the time of discharge, all individuals should be offered voluntary HIV testing and, if they are positive, assistance navigating to treatment sites. It is time to rethink how we treat individuals who have been marginalized and made vulnerable by incarceration for their own health and well-being and for the health and well-being of our communities.

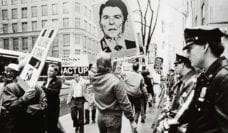

Photo by Anh-Duc Le on Unsplash