Children and adolescents are increasingly interacting with the world through tablets, smartphones, TV, and video games. Ninety-five percent of American adolescents have access to a smartphone, and 45% report being online “almost constantly.” The COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated their use of digital media.

While screen use is an almost unavoidable part of everyday life, potential addictive qualities should be noted. Screen use may veer into problematic territory when one is unable to regulate control over their own use, which can lead to adverse consequences. Studies have shown associations between more screen time and weight gain, cardiometabolic disease, cyberbullying, eating disorders, and poorer mental health. These relationships may be nuanced. But, overall, problematic screen use can contribute to negative impacts on functioning and mental health.

Given the possibility of adverse consequences, it is important to determine the prevalence of problematic screen use and related sociodemographic factors. Only then can appropriate measures be taken to prevent downstream effects on physical, mental, and emotional wellbeing.

With this in mind, we explored problematic screen use in a large, diverse sample of American children, ages 10-14. We analyzed data from the ABCD study, which is surveying almost 12,000 children over multiple years. The study includes questionnaires gauging problematic video game, mobile phone, social media, and general screen use.

Families and communities can work together to prevent problematic levels of screen use – as well as future deleterious outcomes – in our youth.

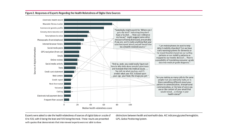

On average, boys reported higher problematic video game use, while girls reported higher problematic social media and mobile phone use. Native American, Black, and Latinx adolescents reported higher problematic use of video games, mobile phones, social media, and overall screens relative to their White peers. Additionally, Asian adolescents reported higher problematic video game use compared with White adolescents.

Lower household income was associated with higher problematic screen use, whereas lower parent education was linked to higher problematic video game use. Adolescents whose parents were unmarried/unpartnered reported higher problematic mobile phone use compared to adolescents whose parents were married/partnered.

Interestingly, while higher household income was protective against problematic video game use, this link was weaker for Black adolescents than White adolescents. The theory of marginalization-related diminished returns may provide a possible explanation. The theory suggests that higher-income Black children may actually be subject to more racism than their lower-income counterparts, as the former group is likelier to live in majority-White neighborhoods.

The American Academy of Pediatrics suggests that families adopt a media use plan to discuss digital media rules and priorities for their household. A family media plan may include, but is not limited to, designating certain areas of the home as screen-free zones, restricting device use at specific times of day, and implementing device curfews. Parental oversight is critical during early adolescence, so parents need to be cognizant of the warning signs of problematic screen use.

Screen use is at an all-time high, with potential harms and benefits. Whether via implementing media use plans, promoting greater physical activity, or government regulation of screen time in child care centers, families and communities can work together to prevent problematic levels of screen use – as well as future deleterious outcomes – in our youth.