If a child sees an ad for a sugary cereal, they are likely to ask for it. They may even beg and whine until the colorful box ends up in their exasperated parent’s shopping cart. This “pester power” can drive family purchases.

Advertisements target children and influence their preferences. Still, no federal laws regulate what foods and drinks can be promoted to kids.

Big food and beverage companies launched the Children’s Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative in 2007. This ongoing initiative is a response to the Institute of Medicine’s report that connected children’s advertising to obesity. Coca-Cola, Kellogg’s, and other companies voluntarily regulate what products appear in children’s advertisements.

Following dietary guidelines from the Department of Agriculture and the Food and Drug Administration, the initiative tightened their nutrition criteria for advertisable products in 2020. These criteria are used to create lists of ad-friendly foods and beverages.

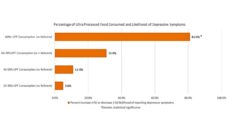

Melissa L. Jensen and colleagues questioned if the initiative’s criteria motivate companies to show their healthiest products on children’s television. The research team used Nutrition Facts labels and ingredient lists on brand websites to evaluate the nutritional content of all products on the initiative’s “nice list.” They then used data on children’s ad viewership and company spending on advertisements to determine which ads were viewed the most on children’s television channels.

The advertising initiative is failing to protect children in multiple ways.

The researchers compared the nutritional content of products that appeared onscreen to those that did not receive airtime. Foods that appeared on children’s television had higher calories, saturated fat, and sodium than those that were not advertised. Instead of promoting their healthier options, like yogurts and low-sugar cereals, initiative members chose to show Goldfish, Pop-Tarts, low-fat Cheetos, and other “nutritionally questionable” items.

Food and drink ads are only regulated if they are intentionally directed towards children. This is another limitation to the initiative. Companies are free to advertise their most unhealthy products in public places, where of course, the ads might be seen by children.

Families in areas that lack grocery stores, namely low-income and predominantly Black or Latinx/Hispanic neighborhoods, may be targeted by food and beverage ads by way of their children. Children living in low-income districts are likely to pass more food and beverage ads on their walks to and from school than children in other schools. Many of these neighborhoods notably rely on fast food or products from corner stores or bodegas. Items that appear on roadside billboards or at bus stops also appear in local stores and restaurants. In turn, adults may give in to their children’s pleas for unhealthy products.

Ads on free online platforms, like YouTube and TikTok, reach children in low-income neighborhoods without access to cable. One instance is Kellogg’s cereal for dinner campaign. A YouTube ad for the campaign shows beloved cereal mascots Tony the Tiger and Toucan Sam encouraging a family with two young children to swap their chicken dinner for a dinner of Frosted Flakes and Froot Loops.

The advertising initiative is failing to protect children in multiple ways. When advertising directly to children, participating companies are not showing their healthiest products. They are also bypassing restrictions set by the initiative and targeting low-income and non-White children in the process.

Researchers Jensen and colleagues suggest that industry self-regulation will not lead to healthier advertising. They recommend that local and state governments take steps to regulate unhealthy food marketing.

Photo via Getty Images