In Massachusetts, people involved with the criminal justice system (i.e., involved with the courts, incarcerated in jail or prison) have 120 times greater risk of overdose death than those who are not involved with the criminal justice system. One way to reduce risk of overdose for this population is to create novel programs in courts that expand access to effective treatment for opioid use disorder, including medication.

To better understand how courts can help reduce harms associated with opioid use, my research team documented one of the first court-based programs in the U.S. that provides access to treatment for opioid use disorder.

The Holyoke Early Access to Recovery and Treatment (HEART) program was launched in January 2021 in Holyoke, Massachusetts, a community of primarily Latinx residents with limited access to health care. The goal of the program is to provide same-day access to medications and other treatment for opioid use disorder for any adult who appears before the court.

During working hours, anyone who enters the court can immediately meet with a peer recovery coach in a private room to discuss treatment options. Certified peer recovery coaches are an essential support for HEART participants because they are in recovery themselves, are from the local community, speak both Spanish and English, and are knowledgeable about local treatment options. To better understand how this unique program works, we interviewed program experts, including court and local opioid treatment program leaders, staff, and participants.

The story of the HEART program offers a model to help other court leaders decide if a program like HEART could be helpful to increase access to treatment in their communities.

Staff and leaders anticipated that many participants would prefer to speak Spanish, so all materials were printed in Spanish and English, and a Spanish-language interpreter was available during all program hours. Overall, staff and leaders were hopeful that the HEART program would connect more court-involved individuals with treatment for opioid use disorder and other important healthcare resources. However, they remained concerned that the program might not be able to engage some groups of people like those who distrust public institutions due to past experiences of racism and discrimination.

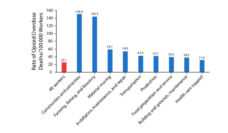

While some of the people appearing before the court were reluctant to accept assistance, participants appreciated that the court offered peer recovery coaches and access to treatment. Specifically, participants liked how knowledgeable the recovery coaches were and how they also provided information on social services (such as employment services and food stamps).

We learned from our interviews that providing many types of treatment options and other services is essential to meet the needs of participants. This is similar to what previous researchers have found. People with opioid use disorder often have complex health needs and essentials, such as access to housing, food, and employment services, are needed to start treatment and to stay in treatment. Without access to these basic needs, engaging in treatment is more difficult.

Historically, opioid use disorder treatment programs for criminal-justice-involved individuals have not considered cultural identity. In contrast, the HEART program was implemented in collaboration with community partners from many institutions and bilingual recovery coaches from diverse backgrounds to better engage Latinx participants. In the future, HEART leaders might consider partnering with faith-based organizations.

Presiding judges, court administrators, and other staff were committed to operating the HEART program and resolving challenges because they anticipated that the program would improve the health of their community. Future research is needed to answer the following questions about HEART participant outcomes: Do participants stay in treatment? Does the program reduce rate of overdose in Holyoke?

The story of the HEART program offers a model to help other court leaders decide if a program like HEART could be helpful to increase access to treatment in their communities.

Photo via Getty Images