In 2021, approximately 43,600 women died from breast cancer, the second leading cause of cancer death in women. Four states — Arizona, Kentucky, Indiana, and Michigan — offer incentives to encourage mammography screening in their Medicaid programs. Incentivizing mammography is ethically complex, especially as women’s autonomy may be undermined if financial incentives are used without the promotion of informed decision-making. We analyzed publicly available information on these states’ programs.

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines recommend screening every 2 years from age 50. Michigan is the only state whose incentive program is consistent with these guidelines. By contrast, Arizona and Kentucky incentivize annual screening from age 40, which is consistent with recommendations from the American College of Radiology and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. In Indiana, one plan incentivizes annual screening from age 35, which is not consistent with any professional guidelines.

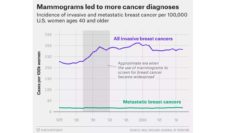

The USPSTF cautions against screening before age 50 and at more frequent intervals because of the increase in potential harms. By screening every year instead of every 2 years, an additional 2 breast cancer deaths per 1000 women can be prevented. However, annual screening, compared to biennial screening, results in an additional 845 false-positive tests, 82 unnecessary biopsies, and 6 over-diagnosed tumors. Moreover, compared to biennial screening from age 50, annual screening from age 40 increases the likelihood of false positives and/or biopsies. Screening data are complex, and low health literacy among Medicaid populations poses further challenges.

To compare the magnitude of the incentives across states, we converted the monetary value of each state’s incentives to the amount of time beneficiaries would have to work at their state’s respective minimum wage.

We found that incentives vary across all four states. Some are structured as rewards such as reduced cost-sharing and others as penalties like disenrollment. To compare the magnitude of the incentives across states, we converted the monetary value of each state’s incentives to the amount of time beneficiaries would have to work at their state’s respective minimum wage. Rewards range from the equivalent of less than one minute of work at state minimum wage to nine days, and penalties range from roughly 2-8 hours. In our ethical appraisal, several elements stand out.

The power of incentives in terms of women’s economic situations is concerning, given how incentives range from 5 cents to $540. The effect of possible disenrollment from a health plan also cannot be understated. Taken together, these consequences may undermine attempts to encourage women to become independent decision-makers in their own health care.

Our findings highlight how financial incentives promoting mammography may lead beneficiaries to accept risks they might otherwise avoid. As incentives increase, policymakers have an obligation to provide beneficiaries with adequate information on the potential harms and benefits of health interventions. Mammography incentive programs monitor changes in screening rates. However, none of the plans we analyzed intends to assess women’s understanding of the potential harms and benefits.

The US Government Accountability Office recently reviewed waiver programs and found that evaluations are lacking in new knowledge generated by these programs. Our findings unfortunately complement this review, as plans for program evaluation are limited. Incentive programs with few safeguards against undue influence are problematic, especially because they are directed at low-income women who tend to have low health literacy.

Moving forward, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (which enabled the mammography incentives) have an obligation to review the variation in incentive designs and ensure they align with professional guidelines. Incentive structures misaligned with evidence-based practices, like incentivizing 35-year-old women, should be stopped immediately. Additionally, an assessment of beneficiaries’ understanding of the potential benefits and harms of screening should be pursued. Finally, states should consider incentives for using evidence-based decision aids, rather than screening, to promote women’s informed decision-making.

Photo via Getty Images