Climate change threatens the personal health and safety of individuals in the United States in a number of ways. Yet, only half of Americans view climate change as a personal threat. While there are very real pragmatic barriers to adopting technologies and behaviors to minimize greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions due to cost and practicality, there are also psychological barriers that are tied up in ideology and worldview that affect personal motivation to act to prevent further global warming and climate change.

While climate change poses a risk to human health and safety, health and safety risk management approaches have not been traditionally applied to address the problem. These approaches in organizational and industrial settings involve evaluating threats and responding with risk treatment actions. Actions are selected from a hierarchy, from most to least effective, where organizations will opt for the most effective risk treatment first prior to considering a less effective intervention, so long as it is within their means to do so.

Health and safety risk management approaches also use a continuous improvement process where organizations assess how effective their actions were in controlling the risk, perform assessments for new threats, and take further risk treatment actions as part of a repetitive cycle. This is what is called a plan-do-check-act cycle in systems safety and organizational systems management. This is how organizations improve the performance of their operations, making them safer and better with every iteration of the cycle.

While there are many differences between organizations and personal and family units, it is reasonable to expect applying this risk management method to personal choices will see similar benefits. Our study set out to test this by assessing how individuals’ personal motivation to act to prevent climate change was affected by communicating it as a health and safety issue that could be improved by personal action through a health and safety risk management approach as described above.

We were interested in understanding the different ways in which people think about climate change. We asked participants if they believe climate change is caused by human activity; if they believe that humans can slow or stop climate change; and if they believe that climate change affects their lives. We also asked participants about their knowledge of the impacts of climate change, if they see it as an important challenge to address, their preferred actions, and personal barriers to taking action.

Carbon neutrality is a journey more likely to be reached by a continuous improvement process where each positive step builds momentum upon the other. It takes several small recurring steps to build good habits.

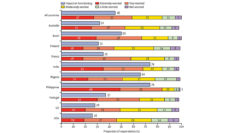

We also evaluated the personal worldview of participants using the work of Mary Douglas and Aaron Wildavsky’s Cultural Theory of Risk and Dan Kahan’s Cultural Cognition Theory. This assessment of personal worldview attempts to score people’s attitudes along two scales: “grid” and “group.” The “grid” scale evaluates attitudes on how goods, offices, duties, and entitlements are distributed. A hierarchist view may tend to support social status based on age, race, gender, bureaucratic office held, or lineage, whereas an egalitarian view is on the opposite end of that scale, where individuals generally believe no-one should be excluded from social roles based on these factors. The “group” scale evaluates attitudes on how far people should be able to rely on themselves and make decisions for themselves versus relying on community or the government, where an individualist worldview is on one end of the scale and a communitarian view is on the other.

We found that personal motivation for action significantly increased after the communication intervention. Feeling personal risk also increased as did believing in human causation and human ability to slow or stop climate change. These were also significant predictors of personal motivation.

Those who prioritized climate change as a health and safety issue and those driven by a desire to protect current and future generations had higher levels of personal motivation than those who didn’t see it as an important problem. Knowledge of climate change also increased and preferences for personal mitigating actions shifted towards more impactful choices, such as opting for emissions-free transportation and energy where possible.

Psychosocial factors as barriers to climate action also decreased after the communication. These barriers include not knowing what to do that will make a difference, concern over disapproval from family or social groups, and having a conflict of interest from an employer or political affiliation. We found participants from all worldviews had higher motivation for action after the communication. We also found holding egalitarian worldviews significantly predicted climate action motivation.

Carbon neutrality is a journey more likely to be reached by a continuous improvement process where each positive step builds momentum upon the other. It takes several small recurring steps to build good habits. By trying to continually improve, and opting for the most effective options where possible first, people can build upon small actions and set goals for more impactful improvements. Because it will take the collective action of people from all worldviews to meet the climate crises, communication about climate change must speak to all worldviews.

Overall, presenting climate change impacts as a health and safety issue and providing people with information on how they can make meaningful improvements to prevent climate change based on several small recurring steps, was effective in improving their attitudes towards climate change and their motivation to take action and may be a useful way to increase public awareness and interest in preventing further climate change.

Photo via Getty Images