Public Health Post: The NRA’s so-called Institute for Legislative Action has written some recent articles that heavily criticize the relationship between public health and gun use in the United States. How can we reason with advocates for gun owners and others who hold strong pro-gun opinions? What can we say to try and find common ground?

David Hemenway: I don’t think it’s useful to think, ‘Oh yes, we’ll be able to work together with the NRA.’ They don’t want to work together with us. They want the U.S. to have lots of guns because they want the industry to be able to produce and sell lots of guns. It’s difficult to find common ground with pro-gun advocacy groups because they have vested interests, and opinions that they’re not going to change.

When our center moves to one-on-one talks with gun owners, gun trainers, gun range owners, and gun shop owners, we find that it’s not difficult to find common ground and to work together at the individual level. In fact, there are many issues and policies and programs where we agree. National surveys over the last 30 years have shown a large majority of Americans, including most gun owners, want reasonable guns laws and programs. From my point of view, the problem is that gun owners too often vote for and give money to people in far-right organizations who never want to compromise.

In a world where guns are the leading cause of death among children and teens, thoughts and prayers reign as the standard reaction for many policymakers. Beyond hope for a better tomorrow, what do policymakers have left to offer to teachers and parents who are concerned for the safety of the young people in their lives?

There are so many things that governments can do. For example, government is key for collecting good data, which is crucial for making good policies and changing public opinion. The government can make the data available and fund research to analyze the data and disseminate the findings.

What the government buys and how it buys also matters. For example, a big success story in motor vehicle injury prevention was airbags. The automotive industry wasn’t putting airbags in cars until the government stepped in. The government was the first major buyer of airbags, and the results provided real-world evidence that airbags were effective and could save many lives. Government can also do some of the basic research, such as on “smart guns” that will only work for the authorized user, and they can then be willing to buy these guns when they are produced.

Your book, Private Guns, Public Health has stayed relevant since it was first published in 2006. Based on the central themes of your book, what has stayed consistent over the years? What, if anything, has improved?

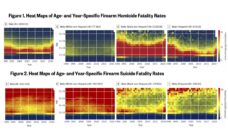

The fact that guns have become increasingly part of the culture wars has been a problem. The fact that the federal government has done so little to reduce gun violence is so frustrating. And red states have weakened their already lax gun laws. But things are improving in some ways. Blue states are passing stronger gun laws, and there is now more funding for gun research. More foundations, universities, hospitals and even some states are funding research. And the National Violent Death Reporting System is now fully funded and provides incredibly useful data on the circumstances of firearm deaths.

Government can do so many other things, though, such as using the bully pulpit. There’s more evidence right now that a gun in the home increases the risk of suicide for everyone in the home than there was about the link between cigarettes and cancer in the 1960s when Surgeon General C. Everett Koop proclaimed that “Smoking is a cause of cancer.” The government could hold hearings and the Surgeon General could produce annual reports about the leading cause of death to our children and young adults. But we don’t do it.

Do you feel like we have enough data and research right now to change public opinion on gun violence?

No, not at all. Guns are bought in society by people who are mostly able to pass a background check, who mostly want them for self-defense. People think the gun is going to really protect you, but the evidence grows stronger every year that having a gun in the home just makes you less safe. But people don’t understand that at all. The constant drumbeat of the findings of new studies can help change public attitudes.

What’s always so sad for me is that to get politicians to do something, typically something bad has to happen to them or their own families, otherwise they don’t care. There’s so little empathy.

Despite the bleak statistics on gun deaths in the United States, people still desire and push for changes. What advice can you offer to public health students and activists who are looking to prevent needless gun-related fatalities? What can we do? How can we make meaning of this?

Most successes in public health, and certainly in injury control, take much longer than you hope. Every time there are three steps forward, there seems to be two steps back. There will always be people fighting against you. If something was easy to do, it would have already been done.

You can spend time alone working on issues or giving your money to the right advocates or voting for the right people. But it’s more effective and more fun when you work in groups. This has been seen for groups of victims and families of victims; they really matter.

So you have to be persistent. It’s often discouraging and there’s no fame or fortune in fighting for public health, but you’re on the side of the angels. And lots of little successes add up. Eventually there is enough impetus and if you are ready, then everything can tip and big changes can happen. There have been so many incredible successes in public health, often due to the persistence of a small number of people.

Photo provided