Think about a metropolitan area like Seattle, Washington, where a little over three million people live. Double that number and you have a relatively accurate count of children living without an adequate or stable food source in the US. Kids are more likely to develop problems in school when their diet consists mostly of food with low nutritional value. The challenge here is that diet is not the only aspect of the home environment that influences child development and behavior. Kids exposed to problems like childhood trauma are more likely to become obese, aggressive, anxious, and depressed, and there may be a close connection between poor diets and difficult home lives while growing up.

Dylan Jackson and his colleagues wanted to know how children experience food quality and trauma. The researchers identified childhood trauma by looking at adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) which include separation or divorce of parents; physical, emotional, or sexual abuse; incarceration of a household member; and mental illness, substance use, or domestic violence in the household. Jackson then counted how many ACEs each child experienced. Finally, the researchers categorized food quality based on whether food in that household was always available and nutritious (no food insecurity), always available but not nutritious (mild insecurity), or not always available (moderate-to-severe).

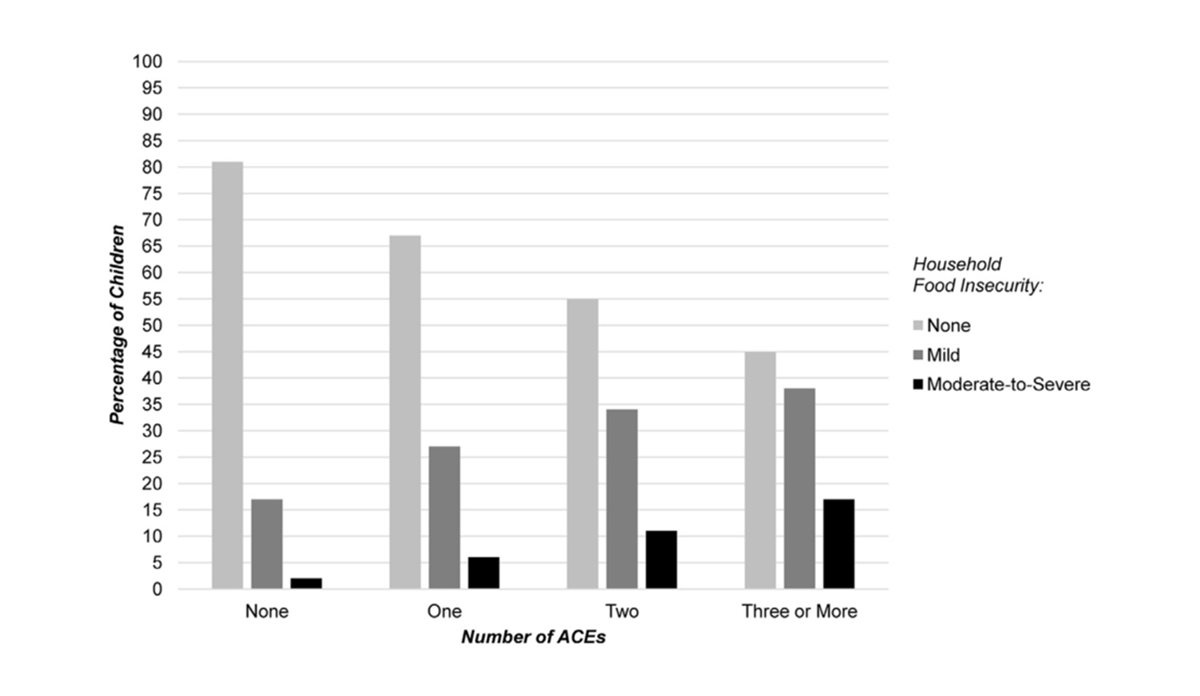

The graph above shows that food insecurity and household trauma went hand-in-hand. Kids from food-secure houses reported fewer traumatic experiences than those with mild and moderate-to-severe food insecurity. These findings suggest that a large proportion of the six million children in the US who lack nutritious food may suffer from the cumulative effects of a chaotic and sometimes dangerous home environment. The success of childhood nutrition assistance programs may be limited by difficulties at home.

Databyte via Jackson, Dylan B., et al. “Adverse Childhood Experiences and Household Food Insecurity: Findings From the 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine, vol. 57, no. 5, 2019, pp. 667–674.