The HIV epidemic in the United States impacts approximately 40,000 new individuals every year — most are gay or bisexual men and transgender people who have sex with men. Minority groups, specifically Black and Latinx men who have sex with men (MSM), bear a disproportionate burden of new HIV diagnoses. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that Black MSM have a one in two chance of acquiring HIV in their lifetime, Latinx a one in four chance.

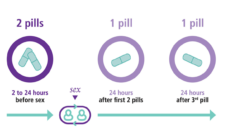

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is a daily pill that, when taken as instructed, provides almost universal protection against HIV. By removing the per-sexual-encounter decision to use a condom or not, PrEP allows individuals to make choices regardless of HIV risk. Unlike condoms, which intrinsically tie the act of HIV prevention to the act of sex, PrEP disaggregates the two.

One can take a pill and not worry about HIV, particularly in the heat of the moment.

The full potential of PrEP is yet to be realized because only a fraction of people who would benefit from taking it have access. Providers helping people access PrEP have reported large drops in use six months after initiation. MSM of color have been less likely to start using PrEP than their white counterparts.

Public health research has an important role to play in understanding differences in PrEP uptake and HIV incidence. By recruiting MSM of color and designing studies that enable adherence to study protocols and daily PrEP use, public health practitioners can proactively dismantle the determinants of the institutional racism plaguing the American health system.

My colleagues and I analyzed demographic and behavioral characteristics associated with completing different study enrollment milestones. We were able to examine racial disparities because 50% of our initial sample were people of color, 13.2 % African American or Black. Because some of our study milestones involved receiving by mail and performing an HIV self-test and then sending it back to a lab, our study highlighted some potential gaps and considerations for home-based sexual screening services.

By ensuring representation of people of color in clinical and behavioral research, we can rest assured that the work of public health is headed towards equality.

Recruiting 50% of participants of color without setting quotas was a major accomplishment of our study. We believe that our methodology and incentive structure was simple and compelling enough to attract all kinds of participants. Despite that, Black participants were less likely to return samples, but the magnitude of this effect was not large. This was a notable difference from other studies, which often report larger rates of non-compliance among Black participants. Our advertisement and study materials were inclusive of all types of men and perhaps that was helpful in recruiting and encouraging participation of men of color. We do not know why Black men were less compliant. However, the success we found in recruiting them indicates positive news to the field, which often relies on oversampling or setting racial quotas.

If we want to broaden the umbrella of HIV prevention, we have to make receiving preventive care as easy as possible. After all, no one is “sick” when they seek prevention services so their participation in research may be an after-thought in their hectic lives. The disparity we observed highlights the importance of including people of color in HIV research, and making it easy for them to adhere to the study protocol. Perhaps if we had made our milestones easier or more convenient, we would not have had this issue.

During the COVID era, and likely for the foreseeable future, home-based healthcare and telehealth will be the norm. We should pay close attention to how to maximize their roles in healthcare in a way that is equal to everyone. Home-based or on-demand services are likely to be a solution in our quest to enroll more MSM, especially Black and Latinx, into PrEP, but only if we can make it easy for patients. For example, young MSM may face challenges related to having or maintaining a fixed address, so we must consider how structural disparities may further exacerbate this challenge.

By ensuring representation of people of color in clinical and behavioral research, we can rest assured that the work of public health is headed towards equality. If we understand the barriers and constraints that communities of color face in starting and maintaining prevention or healthcare habits, we can further inform practitioners on how to best serve these communities. Our study did not go further into teasing out the reasons why participants failed to meet some of the milestones, but we know that for HIV prevention to be successful the community must understand what is at stake for them. Understanding how the messaging of HIV prevention resonates or diverges among communities is essential to deliver interventions and drive uptake.

Photo via Getty Images