Tens of thousands of people face the ice-cold New York City winters each year. Governor Andrew Cuomo used executive action to combat the issue, ordering the state to round up homeless people and place them in shelters on cold winter nights. This is a case of good intentions using a shaky legal foundation. Public health cannot do whatever it wants. Government interventions must be grounded in the law. The classic mode of paternalism will not be effective in the modern landscape and liberty protections must be adhered to.

Paternalistic Law vs. Individual Liberty

Governor Cuomo cites the 77,000 emergency shelter beds available and directs “all local service districts, police agencies including the New York State Police, and state agencies to take all necessary steps to identify individuals reasonably believed to be homeless and unwilling or unable to find the shelter necessary for safety and health in inclement winter weather, and move such individuals to the appropriate sheltered facilities.”

Cuomo’s executive order makes an indirect reference to the state of New York’s police power, which with the Tenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, is a power not delegated to the federal government and thus retained by the state. The police power gives the state the authority to act on behalf of its citizenry to protect the health and well-being of its constituents. Therefore, Cuomo concludes that it is an obligation of the state to protect the particularly vulnerable, which includes the homeless population. But is this grounds for forcible placement of a homeless person in a shelter?

Legal Authority

What, then, are the laws associated with the case? First and foremost, we must examine whether the governor is acting within the bounds of his own and the state’s inherent police power. Secondly, we must weigh this police power against Section One of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution which guarantees to all citizens of the Unites States the protection from state laws that attempt to deprive the citizenry of life, liberty, or property without due process of law. Moreover, Section One guarantees any citizen within the state’s jurisdiction, including the homeless population, equal protection of the laws.

Cuomo defends his authority to put in to effect such orders by citing Sections 28 and 29 of Article 2-B of the New York State Executive Law, which sum up the governor’s power pertaining to post-disaster recovery planning and the direction of state agency assistance in disaster emergencies. Section 29 explicitly states, “…the governor may direct any and all agencies of the state government to provide assistance” upon the declaration of a state disaster emergency. This assistance includes “…making such other use of [the state’s] facilities, equipment, supplies and personnel as may be necessary to assist in coping with the disaster…” Per Governor Cuomo’s description of the situation, it is obvious that he sees the winter weather as a potentially avoidable disaster for the homeless population. These sections of the Executive Law seem to parallel the state’s power to protect the health of its citizens.

As aforementioned, the Fourteenth Amendment protects an individual from the seizure of liberty without due process of law. But if that person were a danger to themselves or others, forcible commitment for a mental health evaluation may be warranted. Under the state’s Mental Hygiene Law, a person’s mental competency must be judged to be compromised before they could be forcibly evaluated. As it pertains to legal precedence, the United States Supreme Court declared in Jacobson v. Massachusetts that the state had the power, in the face of “great dangers,” to restrict the individual liberty granted by the Fourteenth Amendment.

It is notable that the Governor employed the state police to enforce the executive order. This requires improperly trained officers to do on-site, hastily performed evaluations to determine the mental competency of a homeless person, which is simply asking them to operate in a way that is far outside their skill set. As inane as a decision to stay out in the cold might seem, this is a historically underserved population who most often do not have a semblance of exercisable autonomy. This order is just another check on the list of events in the lives of homeless people that they do not have control over.

Future Interventions

If this order and others like it are to be put into effect in order to protect public health, it must be done with three major principles in mind:

- Proper adherence to the law: orders must adhere to limits on legal authority. Some flexibility and discretion exists in law but gross oversteps must be dialed back.

- Properly trained agencies: getting the right people for the job is critical.

- Adequate consideration of a citizen’s right to life and liberty: public health cannot operate in a purely paternalistic approach. Liberty cannot be restricted without due process of law; if a law like this is adjudicated and upheld public health must do the work of narrowly tailoring its approach.

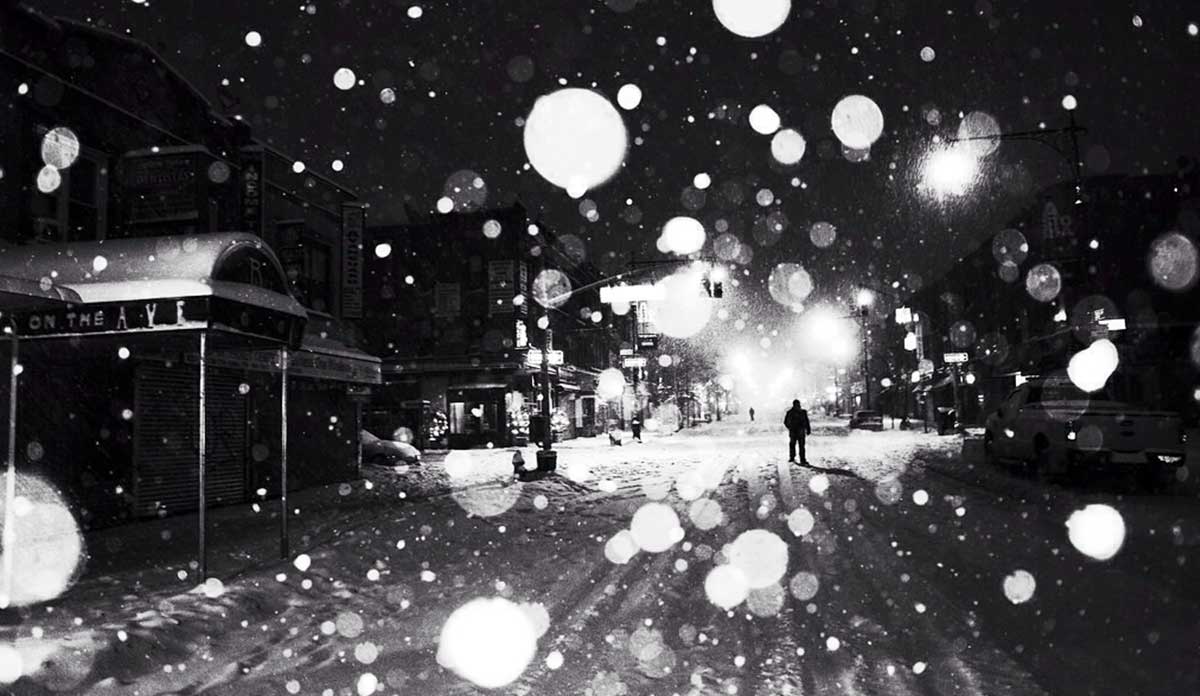

Feature image: Young Sok Yun 윤영석, No cars and snow like stars, Astoria, NY, used under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0