The recent revelation that FamilyTreeDNA is sharing all of its customers’ genetic information with the FBI without the need for a warrant or a court order emphasizes one of our genetic privacy concerns. As the Golden State Killer investigation recently demonstrated, these concerns will be of interest not only to the customers of FamlyTreeDNA, but to their relatives as well.

Unlocking the information hidden in one’s genetic code has clear appeal. One can claim or clarify heritage, diagnose current disease, and learn about the risk of future disease. Since the first direct-to-consumer (DTC) genetic testing company opened its doors, business has expanded in terms of both the number of companies and diversity of genetic information services.

The underreported detriment of DTC genetic testing is that it can be used for unapproved information gathering and population surveillance. Just as law enforcement officers can compel compulsory genetic testing for identification, data submitted to public databases (e.g., GEDmatch, where individuals voluntarily submit genetic information with full knowledge that their information is viewable by the public) and the genetic information gathered as part of clinical or research studies may be at risk for use by law enforcement.

The underreported detriment of DTC genetic testing is that it can be used for unapproved information gathering and population surveillance.

What the FamilyTreeDNA revelation reinforces is that consumers lack control of the information uncovered by DTC genetic testing companies. Some of these companies are setting policies that promise a separate consent for release of information outside the company, but these policies currently lack the force of law.

There are also reasons to be concerned about genetic testing done in clinical settings. The results of genetic testing are protected similarly to other information in an individual’s medical record through the Genetic Information Non-Discrimination Act (GINA) which protects against discrimination in the health insurance market. GINA does not, however, protect individuals in long-term care insurance or life insurance markets. Given that long-term care and life insurers routinely require medical records before they offer coverage, an individual’s genetic information becomes a potential source for raising rates or the denial of coverage.

Given that long-term care and life insurers routinely require medical records before they offer coverage, an individual’s genetic information becomes a potential source for raising rates or the denial of coverage.

Genetic information gathered through research studies may be more protected than information gathered in routine clinical care. When researchers get a Certificate of Confidentiality, which ensures that investigators can never be compelled to re-identify research study participants, additional privacy protections beyond the protection typically afforded to medical records is provided. Genetic information obtained through research can, however, still be used for re-identification purposes even with the added protection of a Certificate of Confidentiality.

Since 2015, the National Institutes of Health has promoted the sharing of de-identified human genomic data and associated phenotypic data for NIH-funded studies to vetted databases through the Genomic Data Sharing Policy. Traditionally de-identified genetic datasets (from which personal identifiers have been removed as required by federal law) afford some privacy protection. However, when de-identified genetic datasets are combined with public databases such as phone book data, an individual’s genetic data can be revealed.

However, when de-identified genetic datasets are combined with public databases such as phone book data, an individual’s genetic data can be revealed.

Relatives of consumers, patients, and research subjects who share genetic data are also at risk. As the use of genetic databases to identify and apprehend the Golden State Killer showed, close genetic relatives can be identified through available genetic information.

An individual’s decision to undergo genetic testing can affect the lives of their genetic relatives, as well as future descendants. These effects will arise most frequently from compulsory genetic testing in law enforcement scenarios, but will also arise when an individual submits genetic samples to public databases. At present, these identifications are most likely to involve law enforcement, but the applications readily apply to other areas including long-term care insurance and life insurance.

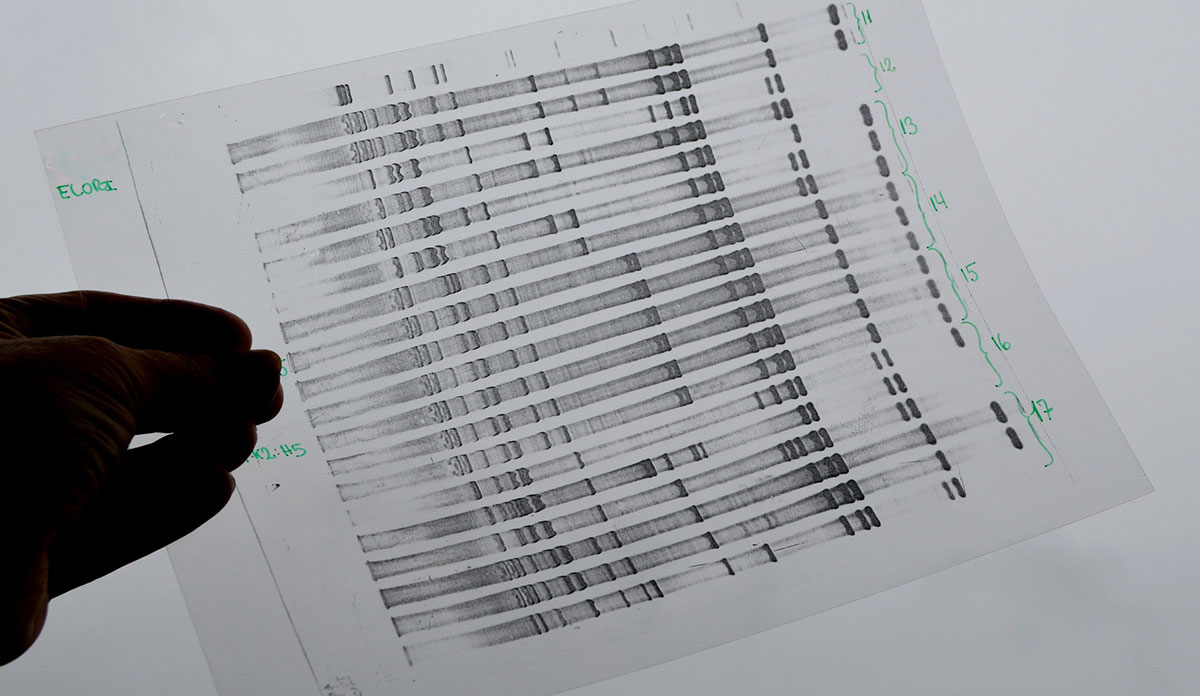

Feature image: Scharvik/iStock