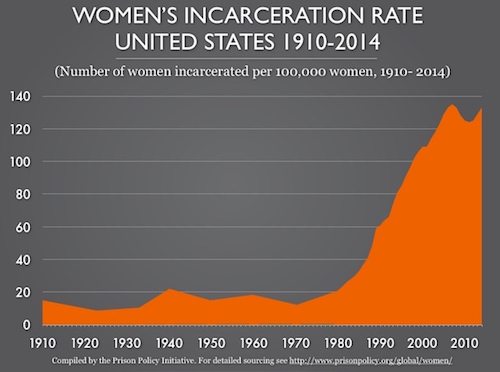

America’s unduly harsh criminal justice approach has led to an unprecedented growth in the prison population, making the country a world leader in incarceration. Since the declaration of the “war on drugs” by President Nixon in 1971, and the re-declaration by President Reagan a decade later with clear rhetoric linked to getting “tough on crime,” the fiscal and social costs have been tremendous. In the decades since, there has been a growing bipartisan consensus around the urgent need to reform the war on drugs policies, particularly the Anti-Drug Abuse Acts of 1986 and 1988. Though some progress has been made on this front, including President Obama granting hundreds of commutations for federal drug offenses, many reform efforts have largely ignored some of the most vulnerable members of society — women of low socioeconomic status and their children. Since these policies have been enacted, the number of female inmates in the U.S. has increased by 646%, at nearly double the rate for men.

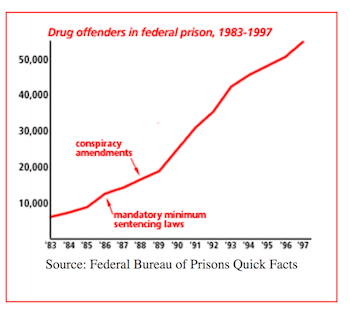

The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 imposed lengthy mandatory minimum sentences in hopes of prosecuting high-level drug offenders. These statutes forced offenders to serve significantly longer prison terms in an effort to deter them from using and selling drugs. Mandatory minimums uniformly tie sanctions based on the quantity of drugs possessed, with no room for judicial discretion. Mitigating factors that would have previously been considered for individualized sentencing such as gender, criminal history, family responsibilities, relationships, community ties, education, and employment, were eliminated.

In the following years, Congress enacted the revamped Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988. The law now applied mandatory minimums to any member of a drug trafficking conspiracy, regardless of how peripheral their role, and held them liable for every act within the broader crime. This resulted in a massive influx of federal drug cases. From 1986 to 1998, the number of federal drug cases increased by 450%. These heavy-handed policies disproportionately target women of low socioeconomic status who are minimally involved with these crimes as the wives, acquaintances, and girlfriends of men using or selling drugs. These women are often considered the “low hanging fruit” of the drug war.

These heavy-handed policies disproportionately target women of low socioeconomic status who are minimally involved with these crimes as the wives, acquaintances, and girlfriends of men using or selling drugs.

Activities such as living where drugs are sold, being present during a drug sale, or counting money are considered part of a drug trafficking conspiracy, and are therefore eligible for harsh mandatory minimums. Due to familial, societal, and financial expectations, women are not able to freely decide whether or not they want to be involved with such illegal activity. The norms and expectations of a relationship constrain a woman to protect her partner from prosecution and contribute to a successful financial and housing status, which may require participation in drug activity. Women will often remain in relationships with men involved with drugs because of the fear of assault, unequal power dynamic, relationship dependency, and a commitment to keeping the family together, even if it puts her at a heightened risk of prosecution and incarceration.

Separate of the high taxpayer cost of enforcement and prosecution, there is a significant social cost. These women can no longer vote, experience difficulty in finding employment, and are removed from their families and communities. After release, these women are denied access to much needed services like federal financial aid, welfare, and federal public housing. They often become trapped in a cycle of incarceration, poverty, and crime. The impact of their imprisonment can be doubly pernicious when it comes to the family, considering that 56% of federal female inmates have children. As a mother becomes incarcerated, children experience separation, anxiety, depression, hyper-vigilance, and shame. Incarceration of a child’s mother leads to a greater risk of involvement in the juvenile justice system, gang activity, and substance use, consequently increasing their risk of imprisonment as adults.

There have been attempts to alleviate the harms of these policies, but many have ignored the unique needs of women and children. An example is the exemption within the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines that allows judges to shorten mandatory minimum sentences if a drug offender provides “substantial assistance” to prosecute other drug offenders. In the past five years, nearly a third of offenders had sentences reduced under these provisions. However, women who are the wives and girlfriends of men tied to the drug trade are often minimally involved, and therefore, less informed and unable to provide any information that is deemed valuable. This exemption often benefits culpable kingpins who have useful information for the investigation.

Meaningful impact could come in the form of gender-specific sentencing reform that would allow for judicial discretion. To break the cycle, there must be a greater investment into education, job training, and post-release rehabilitation specific to the needs of women. However, with the new Administration, any reform efforts can easily be dismantled and likely, will be. Attorney General Jeff Sessions is looking to revamp the “War on Drugs” stating, “Our nation needs to say clearly once again that using drugs is bad. It will destroy your life.” In the context of a justice system disproportionately harming women and mothers, we must ask, what more will this mean for the nation’s women and children?

Feature image: Jobs For Felons Hub, Female in handcuffs black and white, www.JobsForFelonsHub.com, used under CC BY 2.0/cropped from original

Graph: Data Source: This graph is based on a number of different datasets that included women in all types of correctional facilities (including jails) and the total U.S. women’s population for the corresponding year. For detailed sourcing. (Graph: Peter Wagner, 2015) This graph originally appeared in States of Women’s Incarceration: The Global Context.