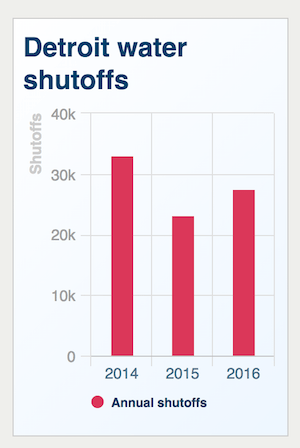

Starting in March of 2014, Detroit residents with overdue water bills could find their water disconnected without warning. Accounts that went unpaid for more than 60 days or owed more than $150 were considered delinquent. The massive water shutoff was Detroit’s unforgiving approach in an attempt to recover $89 million dollars in unpaid water bills. The first year of the campaign resulted in about 33,000 water shutoffs at residential homes. At its peak, 3,000 homes a week lost access.

Renters were sometimes surprised by large water bills that landlords had left unpaid. According to the Detroit News, one Detroit renter, Fayette Coleman, fell victim to a massive, surprise bill. Coleman faithfully paid $23 dollars for water each month. Everything changed in 2013 after the house fell into tax foreclosure. The water bill for the house totaled $7,000. The landlord had failed to pay the water bills (among many other bills), leaving a hefty bill for whoever was left at the address.

The house belonged to the Detroit Land Bank, which was not responsible for paying water bills. The water was shut off because Coleman could not immediately come up with the $700 to enroll in payment program with the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department. If residents are able to pay 10% of the delinquent water bill, then water access is restored. Should residents miss payment deadlines, the percentage of their bills required to turn the water back on rises to 30% and then 50%.

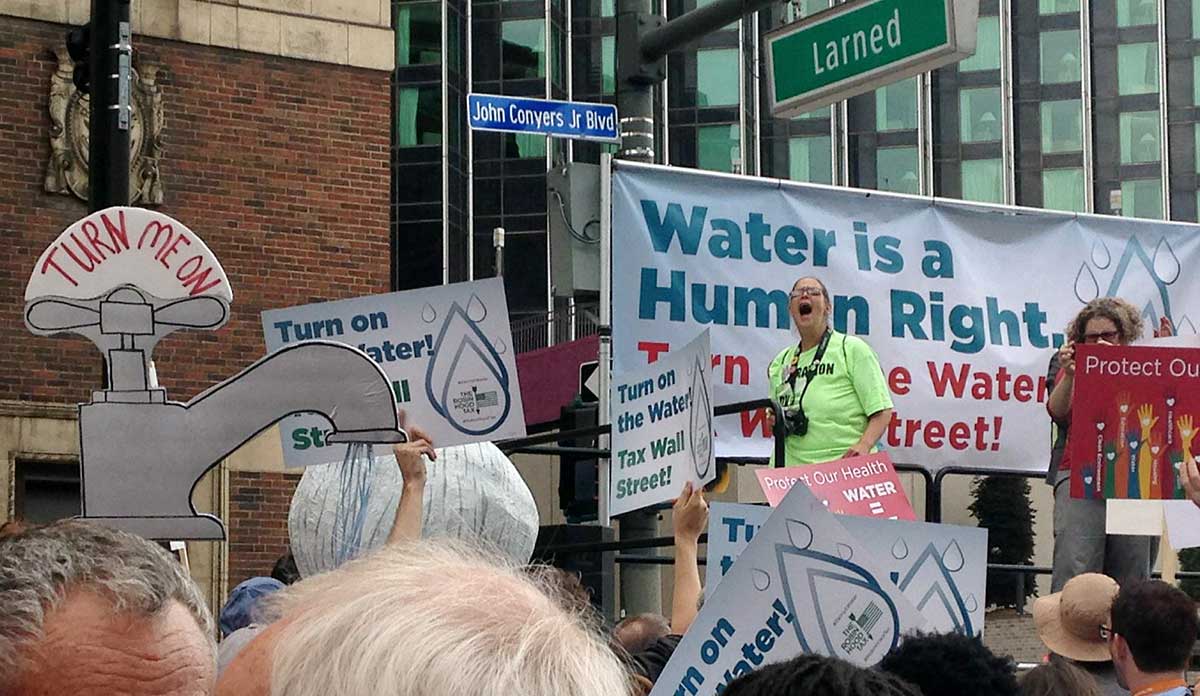

The initial water shutoff campaign drew condemnation from the United Nations (U.N.) and local activists.

The initial water shutoff campaign drew condemnation from the United Nations (U.N.) and local activists. Catarina de Albuquerque, the Special Rapporteur on the Human Right to Water and Sanitation, described it as “contrary to human rights to disconnect water from people who simply do not have the means to pay their bills.” With more than 40% of Detroit residents living in poverty, many found it impossible to pay off large water bills.

Another point of contention for local activists was that residents, who owed a total of $26 million dollars, were targeted more aggressively for water loss than businesses and government-owned properties, which owed $41 million dollars. Only 680 businesses or government-owned properties experienced water shutoffs in 2015 while water at 23,300 residences was terminated.

The Detroit Water and Sewerage Department has no idea exactly how many occupied homes do not have water. They have numbers for how many water shutoffs occur. As many as 44,000 residents have been put on payment plans from 2014 to 2016. However, the exact count of how many homes have been shut off (which would include vacant homes) is hard to know without a door-to-door survey. As of 2016, Detroit News places the number of residences that still were disconnected and were not on a payment plan at 11,800. Monica Lewis Patrick of a local advocacy group called We the People of Detroit places the estimates higher between 17,000 to 24,000 residences.

Health implications of no water

Detroit residents without water are receiving a history lesson in the pre-indoor plumbing era. Residents have to get creative and improvise. Some place buckets on their roofs to collect rainwater to flush their toilets. Some budget $100 dollars a week to buy water bottles. Others bring buckets to fill at their neighbor’s or vacant homes that still have water.

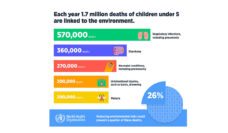

The Henry Ford Global Health Initiative, along with its community partners, recently published a preliminary report on the health implications of Detroit’s water shutoff on residents. The initiative used data from Henry Ford Hospital patients diagnosed with water-associated illnesses such as gastrointestinal issues and skin and soft tissue infections. Patients from blocks experiencing water shutoffs were 1.55 times more likely to be diagnosed with water-associated illnesses. The initiative cautioned that there were limitations to the study. One was that block-level addresses were used, meaning that individual patients were not explicitly linked to a home experiencing water shutoff. The study demonstrates an association, not a causal link, between water shutoffs and water-related illnesses.

Water shutoffs continue

The number of water shutoffs rose again in 2016 to 27,552 after a slight decrease in 2015. As many as one-in-five homes in certain neighborhoods in 2016 were disconnected. This past April, another 18,000 residential accounts were considered delinquent. The Detroit Water and Sewage Department is still owed $122 million dollars from delinquent residential and business water bills.

The number of water shutoffs rose again in 2016 to 27,552 after a slight decrease in 2015. As many as one-in-five homes in certain neighborhoods in 2016 were disconnected. This past April, another 18,000 residential accounts were considered delinquent. The Detroit Water and Sewage Department is still owed $122 million dollars from delinquent residential and business water bills.

Some improvements have been made to the approach Detroit takes to shutting water off: notices, the creation of Water Residential Assistance Program, policies requiring landlords to put bills in tenants’ names, and adding staff at the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department to help residents. According to Detroit Water and Sewerage Department, water was restored within 24 hours at 90% of residences shut off this year by enrolling them a payment or assistance program. As local activists note, verification of this statistic is impossible as the Detroit Water billing department does not have data on where the water is turned back on, just who is enrolled in a payment program. Thousands in Detroit continue to lack access to water.

Water policies in other U.S. cities

There is no national figure of how many residences experience water shutoff. Water shutoffs are hardly unique to Detroit. In 2015, Baltimore issued 25,000 notices for delinquent water, but Baltimore mainly targets customers living outside of the city in the greater county area. In many other cities, including New York City, delinquent water bills are referred to the county treasurer to be included in tax bills or otherwise known as a tax lien. Water is not shut off in these cases.

At the root of the Detroit water shutoff is the question: is water a public utility or a right? Detroit, along with the rest of the U.S., treats water as a public utility by setting a price and reserving the right to control access. A family of four in Detroit pays about 75 dollars a month for water, double the national average. And if bills go unpaid, they remain at risk for losing the water they need to use their bathrooms, wash, and cook.

Feature image: Unitarian Universalist Service Committee, Detroit Water Shutoffs Rally, www.uusc.org/updates/update-on-detroit-water-shutoffs, used under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0