A 2014 letter published in the high-profile medical journal, the Lancet, written by five public health doctors, argued that ‘it is the duty of UK public health institutions to advocate strongly for evidence-based measures to improve the health of society.’ The roots of this idea are long-standing. Rudolph Virchow, a nineteenth century Prussian medic, famously argued that, for medicine to accomplish its aims, ‘it must intervene in political and social life’ to highlight ‘the hindrances that impede the normal social functioning of vital processes, and effect their removal.’ Yet, others in public health are more cautious.

There has been little attempt within contemporary public health to examine what advocacy means in practical terms, who ought to be undertaking this kind of work, or what exactly it involves.

In a recent research article, Ellen Stewart and I explored what public health actors think about the idea of ‘academic advocacy’ by reviewing the literature and examining focus group and interview data with 147 public health professionals (based in academia, the public sector, the voluntary sector, and policy settings in the UK). Our results show there are multiple different ways of thinking about ‘advocacy’ in public health, with a key distinction being between notions of ‘selling’ public health (i.e. ‘we have done the research and it clearly shows that X is now required’) and those that prioritize ‘giving voice’ to communities who otherwise tend not to be heard in public health research and policy discussions. As we set out, risks are involved in both approaches.

If we take, first, the idea that academic advocacy is about ‘selling’ public health solutions, this, at least, seems to be compatible with the popular (and relatively uncontroversial) idea that academics should promote evidence-informed policy responses to the problems they study. As one public health advocate (based in a non-governmental organization) pointed out, ‘as soon as you take [politicians and policymakers] a problem, they want the solution’ and, without that, research evidence is deemed of limited value. However, developing and ‘selling’ public health solutions almost always involves going beyond traditional academic work since academic studies tend to focus on what has happened in the past, not what might/could happen in the future. Moreover, as many of our participants noted, the skills involved in developing policy solutions and in getting (and maintaining) those proposals on policy agendas are not the same as the skills involved in undertaking academic research. And why should we assume that academics have these skills? Indeed, our study provides several examples in which academic efforts to engage in advocacy have backfired and, when this happens, the credibility of the academic, their research, and the proposed policy solution may all be questioned.

There has been little attempt within contemporary public health to examine what advocacy means in practical terms, who ought to be undertaking this kind of work, or what exactly it involves.

Worrying, for some participants, moving into the policy arena created pressure not simply to go beyond the available evidence, but to actively misrepresent it. For others, the need to ensure that policy recommendations were evidence-based, led to a belief that academic advocacy was too often concerned with promoting relatively ineffective, low-level solutions—a far cry from the kinds of radical changes that many interviewees believed necessary to achieve population level health improvements. With such risks in mind, some of those we spoke to believed academics should be wary of any involvement in ‘advocacy.’

If we turn, finally, to advocacy that focuses on ‘giving voice’ to communities whose voices are often unheard, or ignored, in policy and political debates about public health issues, one key issue here is the extent to which community claims/views fit with dominant research claims/views. For issues where these two overlap, this form of advocacy was identified by several participants as particularly important. On the other hand, this was also a form of advocacy that was identified far less frequently by our participants and, perhaps reflecting this, there was little sense of how to undertake this form of advocacy or what to do where views (between different communities, or between publics and researchers) appear to collide.

It is also far less risky for academics to engage in advocacy where they do so alongside others. This kind of collective approach is also more reflective of political science’s accounts of how policy change is achieved.

Some of the risks we identified can be managed. When it comes to the skills involved, for example, it is feasible that we could do more to incorporate relevant training into public health programs (within and beyond universities). It is also far less risky for academics to engage in advocacy where they do so alongside others. This kind of collective approach is also more reflective of political science’s accounts of how policy change is achieved. But while this may work for issues around which there is already a great deal of cross-sector momentum, and multi-disciplinary research, such as tobacco control, it might not be an option for those of us working on more complex, cross-cutting areas of public health, such as health equity and the social determinants.

We should remember too, as many of our participants pointed out, that public health risks also exist if we choose not to engage in advocacy, most obviously the risk that the problems we study are left unchecked. And many of those we spoke to confessed that they struggled to see ‘the point’ of public health research if it was not about trying to effect change in some way.

Overall, our findings suggest that it might be helpful to view ‘advocacy’ as a spectrum of activities within public health and, while there remains much debate as to the appropriate (and desirable) location for academics on this spectrum, we are clearly a long way from the era in which Austin Bradford-Hill, one of the first researchers to identify the link between smoking and lung cancer, reflected that even basic dissemination might be perceived as ‘propaganda.’ Indeed, virtually everyone we encountered seemed to feel that public health researchers have a duty to do more than simply study public health concerns: for some, it might be enough to ensure that the findings of studies are effectively communicated to public and policy audiences but, for others, advocacy may involve a host of strategic and/or dialogic activities intended to transform the way society and policymakers respond to the causes of poor health and premature mortality. In either case, current training programs could be substantially strengthened.

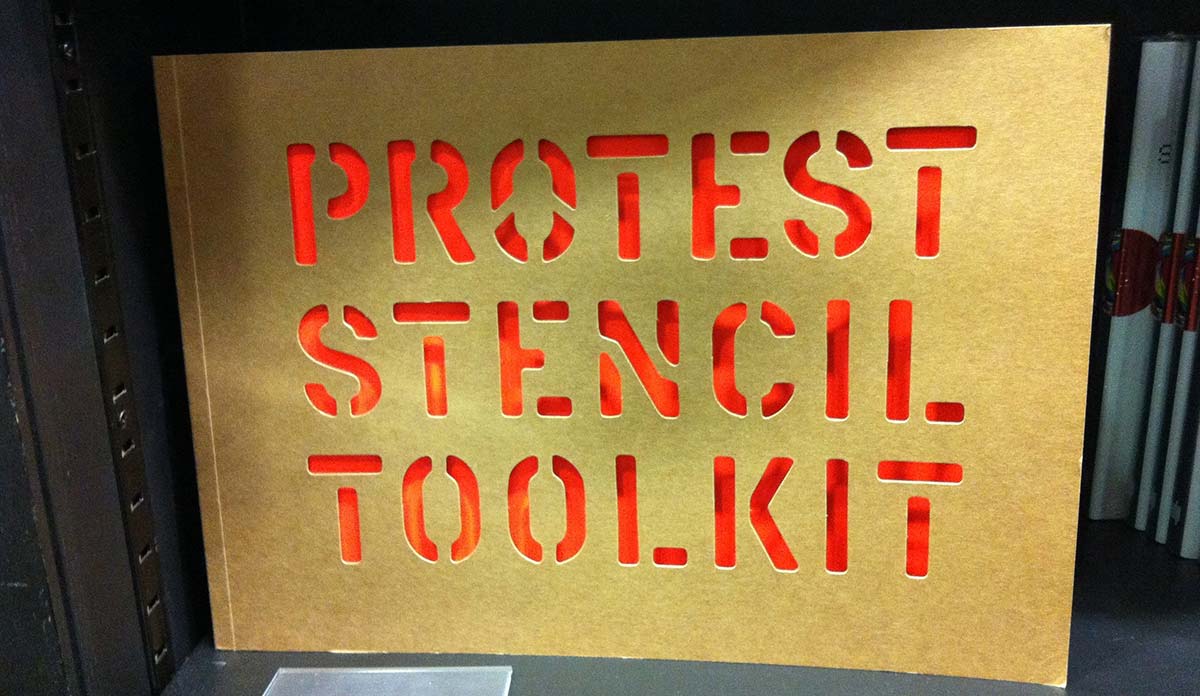

Feature image Joanna Penn, Protest stencil toolkit, Book seen at Waterstones, Covent Garden London, used under CC BY 2.0