In 1867, the United States purchased Alaska from Russia without consent from the Native populations who thrived there long before European invasion. The treaty stated “the uncivilized tribes” would be subject to US laws and regulations. Over the next 150 years, the US displaced and oppressed indigenous Alaskans belonging to 229 unique tribes in order to gain access to natural resources such as oil, whaling, seal fur, salmon, and gold. In exchange, they offered violence, disease, sexual abuse, family separation, and ethnic cleansing.

The severe cultural, social, and economic disruption spurred a suicide epidemic. Today, suicide is the fourth leading cause of death for Alaska Natives. Indigenous Alaskans are 17 times more likely to die by suicide than non-native US citizens, a rate 3.5 times higher than any other ethnic group and 2.5 times higher than non-native Alaskans. For Native Alaskan youth between the ages of 15 and 24, suicide is the leading cause of death.

Suicide rates among Native Alaskans parallel the history of colonization. Colonization not only robbed indigenous people of land and livelihoods, it stripped entire populations of their identity, hope, and future aspirations. It disrupted the social and familial connections that typically protect mental health, especially important for adolescents. With each wave of colonial trauma, the wellbeing of Native tribes receded, despite their enduring resilience. Colonization has been linked to multigenerational trauma throughout the polar North and the world.

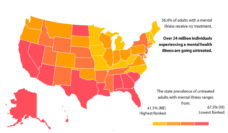

Efforts by the US to address the mental health crisis have only made matters worse. The Indian Health Service is inadequately funded, leaving only 1 in 5 Native Alaskans with access to formal mental health services. Those able to access care face discrimination and treatment that is insensitive to their needs and culture. Dr. Lisa Wexler and colleagues have spent years extensively researching suicide and mental health care in the Native communities of Alaska. Again and again, they found that the Westernized clinical approach to care was not only failing to help but also causing additional harm.

Federal programs have inflicted harm on Native Alaskans for generations.

For example, in the event of a suicide attempt, youth are often isolated, swiftly removed from their community, and sent to a city hospital or to the contiguous states, cut off from their family and social support. Interviews with community members revealed that many Native Alaskans fear seeking treatment: “People know, if they call the cops or go to the clinic, they’re going to get put in the hospital in that one room where it’s all padded.”

Prescribing Westernized mental health care for Native Alaskans is not only culturally inappropriate, it overrides the social and cultural strength they inherently possess. Working directly with Native tribes, Dr. Wexler and her team pulled back regimented clinical interventions, instead allowing Native communities to direct their own care. The community-led program fosters self-determination, as one participant describes – “instead of assimilation…this is what we choose. This is where we want to go with our culture.”

To decolonize their mental health, tribal members gained access to the research on their communities, with the help of Dr. Wexler and her colleagues. The participants disseminate the information, helping those around them take actionable steps to support the mental wellbeing of family and friends. This approach has had a positive impact for program participants and their social circles, creating a ripple effect on the mental health of entire communities.

Suicide is often perceived as a result of psychological illness. We now understand that suicide is more often a symptom of social hardship in the absence of support. Federal programs have inflicted harm on Native Alaskans for generations. Mental health support for Native Alaskans should focus on undoing harm and giving back stolen freedoms and futures.

Photo via Getty Images