When a Florida 12-year-old named Rebecca Sedwick died by suicide, her death made news across the country. It was a story that by 2013 had become too familiar, a tragic early suicide preceded by cyberbullying.

News coverage associating cyberbullying with suicide serves several functions. It draws attention to the harms associated with bullying and alerts schools and families to risks associated with technology use. However, repeated and overly simplistic news coverage of suicide may have serious consequences.

The term “suicide contagion” refers to how one suicide may lead to other attempts. Extensive news coverage of a celebrity suicide, for instance, has been associated with increases in suicides soon after. Other research has shown that not just the number of news stories but also the content can affect suicide rates. Stories describing exactly how a suicide occurred or indicating a sole cause of suicide can to do more harm.

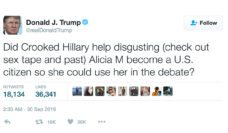

In our study of US news stories, we found that, in headlines like “Bullied to Death,” newspapers across the country mapped a clear path from cyberbullying to suicide. This narrative was reinforced when news stories emphasized the frequency of suicides, stating, for instance, that cyberbullying often led to suicide. Many articles also described in detail how the suicide was completed.

Hearing repeatedly that cyberbullying causes suicide can also create a link in the mind suggesting that one is the natural consequence of the other.

Researchers worry about these portrayals of adolescent suicide in news and pop culture for several reasons. Adolescents are thought to be particularly vulnerable to suicide contagion. Concerns about suicide contagion led to criticisms of the Netflix show 13 Reasons Why. Based on the young adult novel of the same name, the show tells the story of a bullied girl who writes letters to her tormentors blaming them for her suicide. Teens are impressionable and impetuous, and they are also more likely to model behavior from peers or others they admire. Repeated news coverage that names victims suggests the kind of attention suicide might bring. Hearing repeatedly that cyberbullying causes suicide can also create a link in the mind suggesting that one is the natural consequence of the other.

Our study found little reference to other causes of suicide or to solutions or resources that help adolescents cope. Factors known to contribute to suicide, like depression or other mental illness, were rarely mentioned, and few stories offered audiences resources for coping with either cyberbullying or suicidal thoughts. Underplaying mental health concerns in teen suicides may mean less attention to the need for mental health services for adolescents.

The goal of our study was not to cast blame on journalists, an easy target for many in health communication. Instead, we wanted to draw attention to how coverage of cyberbullying also includes reference to suicide.

As a former journalist, I understand the pressures journalists are under. They contend with quick deadlines, lack of expertise in health and risk, and public demand for news that makes sense of complex events. In many ways, their cyberbullying coverage adheres to what we expect from news – foregrounding important social issues, alerting audiences to risks, and giving voice to families and friends who have suffered a tragedy and are pressing for change. The goal of our study was not to cast blame on journalists, an easy target for many in health communication. Instead, we wanted to draw attention to how coverage of cyberbullying also includes reference to suicide. Thinking of cyberbullying coverage as suicide coverage may make public health officials and journalists more sensitive to the issues involved with covering suicide safely.

Organizations such as the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention have published well-researched guidelines for how journalists should, and shouldn’t, cover suicides. Public health professionals focused on suicide prevention should continue to remind journalists about why these guidelines are important. When journalists understand how best to cover suicide to avoid contagion, they can add important qualifications to their work, like emphasizing that there is no one reason why someone attempts suicide. Public health professionals can proactively provide journalists with vetted resources for bullying and suicide prevention and encourage them to include links to further information and resources their stories. Adhering to guidelines when covering suicide, steering clear of inflammatory or overly simplistic language, and telling stories of teens who triumphed over bullying can also help.

Feature image: niclas, Reporter’s Notebook, U.S. version (detail), used under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

If you are having thoughts of suicide, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 or visit suicidepreventionlifeline.org.