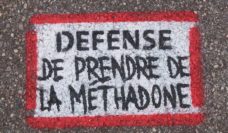

In early October, District Judge Gerald McHugh ruled that Safehouse, a proposal in Philadelphia for a space where individuals can consume illegal drugs they carry while being monitored by a health professional, does not violate federal law. McHugh wrote: “The ultimate goal of Safehouse’s proposed operation is to reduce drug use, not facilitate it.” While the historic decision is certain to be appealed, it may push cities around the country to more seriously consider this critical harm reduction option.

Safehouse is an example of a safe consumption space, set in the neighborhood where 15% of the city’s fatal overdoses happen. Supervised drug use locations have a few main goals. First, they allow for immediate responses to accidental overdoses, saving lives. Second, they link clients to treatment and other social services. Lastly, they prevent disease transmission by ensuring use of sterile needles.

For decades, these facilities have been operating internationally in Canada, Australia, and Europe. In 2014, a comprehensive review of 75 research articles found them to be effective in meeting their primary goals. All studies concluded that they attract the most marginalized substance users, reduce overdose rates, and improve connections to primary healthcare resources. The facilities were not associated with increases in crime or other illicit drug use–two common critiques.

Before the Philadelphia ruling, the wealth of evidence documenting positive outcomes had failed to supersede legal and ideological barriers in the US. Despite multiple city- and state-level proposals, federal officials have threatened lawsuits if the facilities were to open. Prosecutors in the Philadelphia case argued a provision of the Controlled Substances Act, often referred to as the Crack House provision, makes it illegal to own or operate a space where drugs are consumed. In 2018, a poll found that just 29% of Americans supported the opening of a safe consumption space in their community.

The Journal of Urban Health devoted a recent issue to overdose prevention research. Two of the articles report the perspectives of drug users about their willingness to use safe injection sites and community members about the possibility of having one in their neighborhood.

All studies concluded that they attract the most marginalized substance users, reduce overdose rates, and improve connections to primary healthcare resources. The facilities were not associated with increases in crime or other illicit drug use–two common critiques.

For the first study, researchers spoke with 326 people who use drugs in Baltimore, Providence, and Boston. Most (77%) participants said they were willing to use a supervised facility. Women, racial minorities, and people who reported using drugs in public places were most likely to indicate support. The most commonly anticipated concerns included fear of arrest, privacy, and safety, although one quarter of the study participants expressed no concerns.

Researchers in the second study spoke to 360 residents and 79 business owners or workers in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, the proposed site for Safehouse. Ninety percent of residents supported the Safehouse proposal, as did 63% of business owners–far above the national average. Similar proportions believed multiple locations should exist throughout Philadelphia. Support increased when participants were informed of the public health benefits, including reduced overdose deaths, public injections, and discarded syringes.

For individuals who use drugs, given the constant threat of overdose, support for safe consumption spaces may not be surprising. But the pending legal battle aside, strong community support will be necessary to establish Safehouse in Philadelphia or others like it throughout the country.

Photo by Jonathan Gonzalez on Unsplash