For years, an industrial factory named ChemFab was under pressure from the state of Vermont for violating numerous environmental regulations. Rather than clean up their act, they found a new owner and moved everything to their location in a state with fewer restrictions. That place is along the Merrimack River in New Hampshire, where they are still operating.

Under the new name of Saint-Gobain Performance Plastics, the company continues to produce weatherproofed fabrics. In order to give products their water-repelling ability, Saint-Gobain uses Teflon, a product made from a family of chemicals called per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances, collectively referred to as PFAS. PFAS are synthetic chemicals that cannot be filtered by regular water treatment plants. This means that they end up in our soil and drinking water. The human body’s internal filtration systems (the liver, kidneys, and spleen) also cannot filter or break down the long-chain carbon molecules. As a result, PFAS accumulate in the body over time, causing physiological harm.

The Merrimack River in New Hampshire is a source of drinking water for over 500,000 people. The water was tested for PFAS in 2016 after decades of contamination and human consumption. Depending on the location, PFAS levels were 100 to 400 times higher than recommended safety thresholds. Over the following years, 30% of tested wells were revealed to contain dangerous levels of PFAS, high enough to require the city of Merrimack to provide bottled water to affected residents. The state of New Hampshire acknowledged that the Saint-Gobain factory was responsible for the contamination, although the company never formally admitted liability.

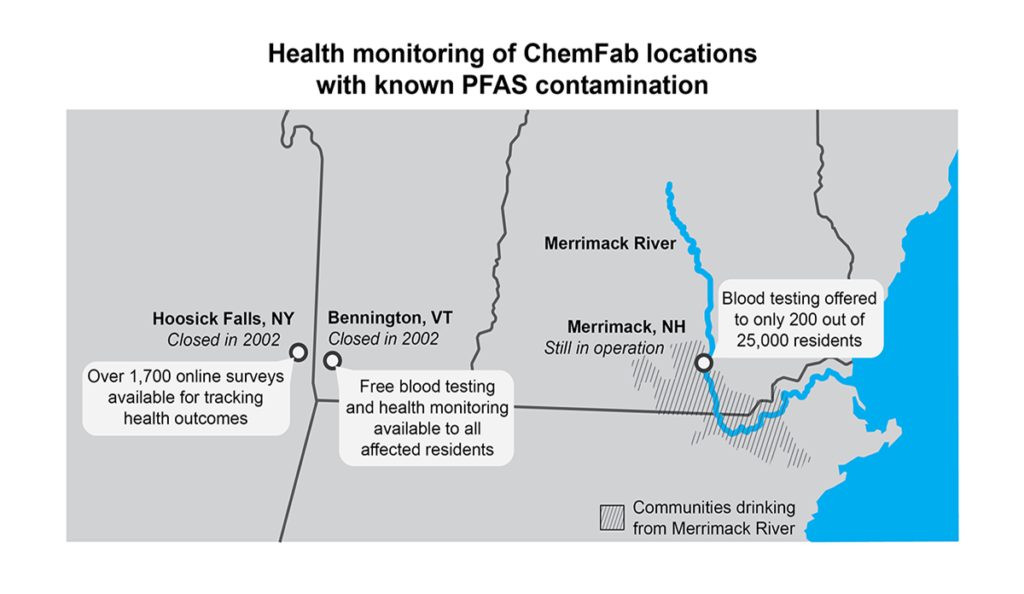

The original company, ChemFab, has had three locations linked to PFAS contamination. The Bennington, Vermont and Hoosick Falls, New York locations closed in 2002 when Saint-Gobain purchased the company from ChemFab and consolidated operations in Merrimack. Both New York and Vermont have since conducted widespread blood testing and community health outcome monitoring. Meanwhile, the Merrimack location remains open and residents have faced an uphill battle against the state in a fight to have more comprehensive health monitoring. After complaints from the Merrimack community, the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services made an offer to sample blood tests from just 200 people, claiming that a larger study would be too costly.

Without support from state or federal agencies, a community-led organization took it upon themselves to conduct a larger health survey of over 500 residents. The local activists first sought input from the Boston University School of Public Health for help designing the survey and later received assistance from the University of Vermont to interpret the results. The survey revealed higher incidence of autoimmune, kidney, liver, developmental, and reproductive disease among Merrimack residents compared to levels in the general population. The reported health outcomes occurred at higher rates for longtime Merrimack residents compared to newer residents.

Although still a relatively small sample, the results corroborate findings from larger studies on the health effects of PFAS, notably the study of 69,000 residents conducted after the incident of contamination in West Virginia by the chemical company DuPont.

PFAS are synthetic chemicals that cannot be filtered by regular water treatment plants. This means that they end up in our soil and drinking water.

PFAS water contamination is suspected to be widespread across the US, but proper response, regulation, and health monitoring is not. New Hampshire has made progress in strengthening PFAS standards, passing its first enforceable regulation in January of 2019. Community members hope that evidence of negative health effects will pressure New Hampshire to provide the residents of Merrimack with further monitoring, physician support, additional health studies, and safe drinking water once and for all.

Photo via Getty Images