Hunger costs the United States approximately $178.9 billion each year. This cost largely stems from the well-documented effects of food insecurity on a child’s physical, mental, and social-emotional development. Food insecurity has been associated with a greater risk of asthma and other chronic health conditions, low birth weight, maternal depression, depression, anxiety, and misconduct. Hungry children are less able to focus and learn. Ultimately, this lack of opportunity for long-term academic success and economic opportunity can perpetuate conditions of food insecurity for future generations.

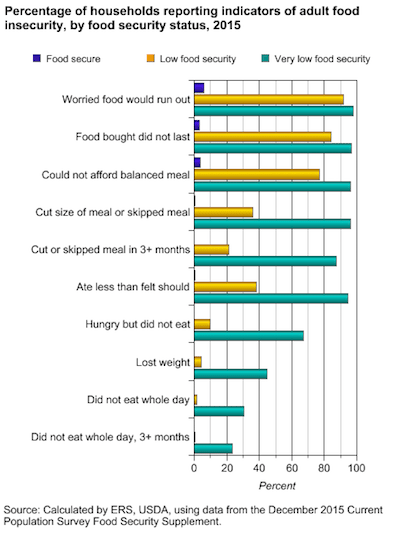

In 2015, 87.3% of U.S. households were food secure, meaning they had “access, at all times, to enough food for an active healthy life for all household members.” That percentage might seem like a healthy majority. Yet that leaves 12.7% of households—48 million people—experiencing some level of food insecurity. In more detail, 7.7% (9.5 million households) experience low food security, defined as reduced quality, variety, or desirability of diet, and 5% (6.3 million households) experience very low food security, defined as having disrupted eating patterns and reduced food intake.

Households with children are significantly more likely to experience food insecurity than those without (16.6% as compared to 10.9%). Despite policy measures to support families with young children, about one in five households with children under 6 worry that food will run out, cannot afford a balanced meal, or are forced to cut or skip meals.

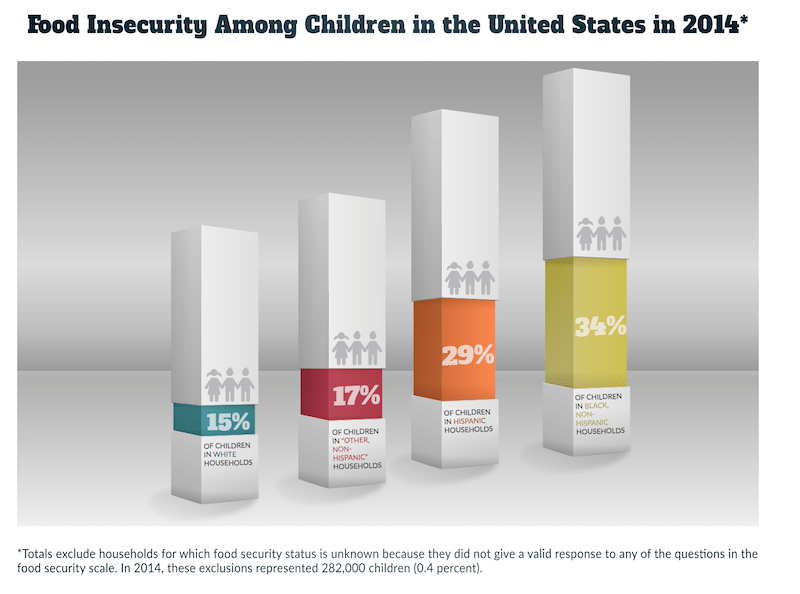

These trends have distinctive effects on racial minorities and those of Hispanic origin, as highlighted by the Center for the Study of Social Policy’s 2016 Report. An African-American child is twice as likely to experience food insecurity as a white child (27% versus 14%). And nearly 25% of food insecure children are Hispanic. The proportion of children experiencing the most extreme food insecurity is about 3 times higher in Black or Hispanic households than in white households.

These trends have distinctive effects on racial minorities and those of Hispanic origin, as highlighted by the Center for the Study of Social Policy’s 2016 Report. An African-American child is twice as likely to experience food insecurity as a white child (27% versus 14%). And nearly 25% of food insecure children are Hispanic. The proportion of children experiencing the most extreme food insecurity is about 3 times higher in Black or Hispanic households than in white households.

Local efforts, state funding initiatives, and national policies increasingly promote installation of grocery stores in food deserts — neighborhoods barren of fresh foods. And while ensuring access to fresh foods is a necessary component to the eradication of food insecurity, it is a comparably easy fix as compared to what recent studies have declared is the deeper issue at play. Research teams like those of Stephen Cummins and Jason P. Block find that policy-level actions like improved nutrition standards for school lunch programs and incentivizing healthy food choices within nutrition assistance programs like SNAP will help food insecure families to actually choose those healthier options. These population-level policy changes will be the key to helping families break away from the debilitating effects of malnutrition and hunger.

Feature image: U.S. Department of Agriculture, 20140711-OSEC-LSC-0615. Students at Hamilton Elementary Middle School in Baltimore, MD enjoy the Summer Food Service Program (SFSP) on Friday, Jul. 11, 2014 in Baltimore, Maryland. USDA photo by Lance Cheung, used under Public Domain Mark 1.0/cropped from original

Graph showing adult food insecurity from USDA Economic Research Service

Graph showing food insecurity among children from Center for the Study of Social Policy