In 2005, five-year old Jaisha Atkins was put in handcuffs after throwing a temper tantrum in her kindergarten classroom. In 2007, 15-year old Aisha was searched, slammed against a wall, and taken to the police precinct for “roaming the halls.” And in 2015, 16-year old Shakara was ripped from her desk and pushed to the ground for using her phone in class.

These incidents represent the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the violence inflicted on young people by “School Resource Officers” (SROs). SROs date back to the 1950s, when their purpose was to provide security at newly integrated schools and foster better relationships between police officers and youth. Decades later, school shootings like the Columbine massacre galvanized a nationwide push to hire more SROs to keep schools safe. As of 2016, 65% of secondary schools had a law enforcement officer.

One study suggests that students develop more positive attitudes towards the police when they have casual opportunities to talk with and receive help from SROs. However, students with more SRO interactions also experienced more frequent school violence. Furthermore, there is little evidence SROs can protect students during school shootings. Among nearly 200 incidents of gun violence between 1999-2018, school officers successfully intervened only twice.

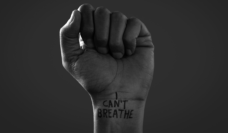

SROs are meant to promote safety, but more often end up punishing mostly Black, Brown, and differently abled children in the classroom. The mere presence of SROs can trigger anxiety, fear, and trauma, particularly for Black and Brown youth. Additionally, SROs often arrest students for minor behavioral outbursts or non-criminal incidents, which feeds the school-to-prison pipeline. In fact, more than a quarter million youth faced legal consequences for school behavior that could have been handled by a conversation with school administrators.

The troubling lack of evidence that SROs increase school safety has researchers and advocates looking for alternatives.

Despite the negative impact of SROs on students’ wellbeing, federal and state governments continue to fund school police officers. Gottfredson et. al analyzed the impacts of funding from the U.S. Department of Justice on SRO staffing and disciplinary actions in public middle and high schools in California between 2011 and 2017. Comparison schools had similar demographics and disciplinary records, but did not receive federal funds for SROs.

Schools that received federal funds had police officers patrolling their hallways more than twice as many hours per week compared to schools that did not receive DOJ grants. Schools receiving SRO grants also had more weapon- and drug-related offenses. The authors suggest several mechanisms to explain these increased crime levels. First, police presence can weaken students’ sense of community and relationships with school administrators. This may create an environment of distrust and increase behavioral incidents. Secondly, the presence of SROs could increase reporting of school crime. SROs tend to be more punishment-oriented, meaning officers frequently view and react to minor offenses with force, which leads to documentation.

The researchers found that SROs rarely have formal protocols for handling school incidents. Only 10% of the contracts between schools and law enforcement agencies described if and when officers should use physical or chemical restraints on students.

The troubling lack of evidence that SROs increase school safety has researchers and advocates looking for alternatives. These solutions largely focus on creating a positive school environment by strengthening feelings of connection between students, teachers, and families.

For example, in Shreveport, Louisiana, a group of fathers formed Dads on Duty in response to violent student fights and arrests at Southwood High. These dedicated parents patrol the school every morning, participate in extracurricular activities, help spread positivity, and have been credited with lessening violence at the school. Peer mediation training is another solution, in which students learn how to resolve conflicts among their peers. Peer mediation programs boost students’ sense of well-being and help to decrease school violence.

For Jaisha, Aisha, Shakara, and countless other youth, SROs perpetrate violence rather than prevent it. Armed officers, it seems, may not be the solution to improving school safety. Instead, bringing in adults who can more positively engage with students (e.g., trauma counselors and social workers), and fostering peer relationships, can create a school community that supports and protects one another.

Photo via Getty Images