Pregnancy, birth, and becoming a new parent is a trying experience for anyone. But imagine also not being able to hear what the doctor and nurses are saying.

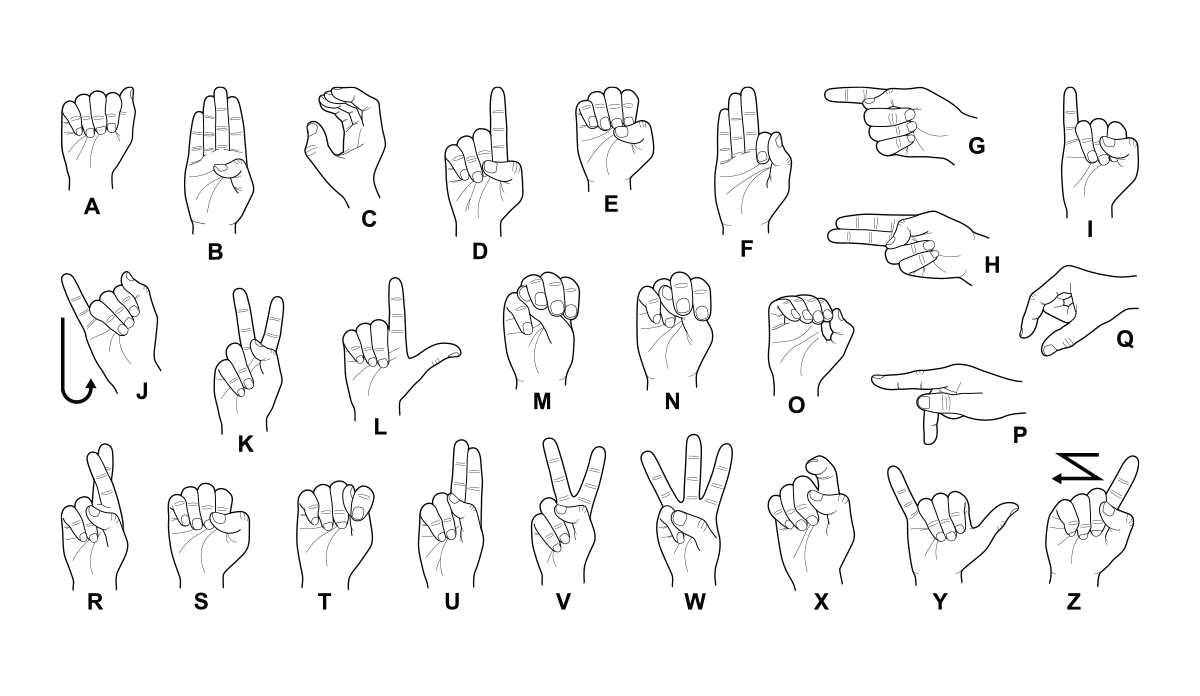

Individual stories vary, but ineffective communication with health care providers is a common theme for the one in six American adults who report hearing loss. Hospitals often fail to provide adequate and appropriate accommodations for patients who rely on American Sign Language for communication. Doctors might only write spare notes or wrongly assume the patient can lip-read. A sign language interpreter may not be hired because the hospital won’t be reimbursed for the cost. As a result, deaf and hard-of-hearing patients are more likely to report experiences of poor communication with health care providers than hearing patients.

Little is known about how the experience of being deaf or hard-of-hearing manifests in maternal and infant health outcomes. To help shed light on the matter, researchers evaluated birth certificates in Massachusetts from 1998 to 2013. Looking at reported health outcomes, they found that deaf and hard-of-hearing women experienced higher rates of multiple pregnancy-related conditions compared to hearing mothers, including diabetes and pre-eclampsia. Their newborns experienced higher rates of adverse health outcomes including preterm birth, low birth weight, and low scores on infant health evaluations, such as the Apgar score.

The health risks of being deaf or hard-of-hearing begin well before pregnancy. The study showed that deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals were more likely to experience social disadvantages such as low education, low income, and lack of a partner. At the time of delivery, mothers experienced higher rates of placental abruption, need for cesarean delivery, and prolonged hospital stay.

Patient-centered care for deaf and hard-of-hearing parents requires communication that is effective, appropriate, and takes into account individual preferences in order to improve health outcomes for both mothers and infants.

Additionally, the health consequences are not entirely physical. Being deaf or hard-of-hearing in a primarily hearing world can be an isolating and lonely experience. Mothers reported higher rates of stress, depression and anxiety both prior to birth and throughout postpartum recovery.

Although some health risks have biological or genetic links with hearing loss, researchers believe it is likely that inadequate communication is contributing to worse health outcomes for an already marginalized population of mothers. Studies have shown that effective communication between patient and provider directly influences health outcomes.

The Americans with Disabilities Act requires that all institutions “communicate effectively with people who have communication disabilities.” Yet, only 17 percent of deaf and hard-of-hearing patients are provided with sign language interpreters. Even when an interpreter or technological assistance is available, many providers fail to utilize help appropriately. The doctor may speak directly to the interpreter, rather than to the patient, leading to them feeling frustrated and ignored. When seeking prenatal care and education, parents may be assigned a different interpreter for each visit, resulting in inconsistent care and communication.

Deaf and hard-of-hearing patients have reported feeling treated as if they are of lower intelligence, when more accurately they are a language minority that differs from those that communicate through spoken English. Patient-centered care for deaf and hard-of-hearing parents requires communication that is effective, appropriate, and takes into account individual preferences in order to improve health outcomes for both mothers and infants.

Photo via Getty Images