Traffic stops are the most common type of police interaction. No one enjoys the experience of being pulled over — the stress of wondering what’s about to happen, the anxiety of a possible ticket or arrest. For Black drivers, traffic stops are more frequent and more likely to result in physical harm by police.

Seat belt laws are one example of how law enforcement in the US is rife with racial discrimination. Over the past two decades, 35 states implemented stricter seat belt laws – the laws that inspired the Click-it-or-Ticket safety campaigns. For most states, the stricter laws reflect a change from secondary to primary enforcement, meaning drivers can be pulled over solely for not wearing a seat belt. Under secondary enforcement, drivers must commit another traffic violation in order to be charged for not buckling up. Switching from secondary to primary enforcement has proven ineffective at reducing fatalities. Instead, strict seat belts laws appear to be a tool for racial profiling.

South Carolina switched to primary enforcement in 2005. Corinne A. Riddell and colleagues examined traffic stop data before and after enactment of the new law. Their study revealed a racial divide in enforcement of traffic laws in the state, occurring both before and after the switch.

For example, the stricter seat belt law resulted in more traffic stops for all drivers because it provided police with an entirely new reason to pull someone over. Black drivers saw a 5% greater increase in stops than white drivers – almost 2,000 more traffic stops in just the first year – despite similar seat belt usage between groups.

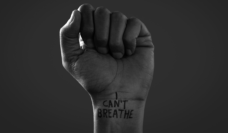

Unequal enforcement of any law is racist. But unwarranted stops and searches are also unconstitutional.

The study also uncovered prior existing racial disparities in vehicle searches during traffic stops. Before the new seatbelt law, drivers were more likely to have their vehicle searched because police could not make an arrest on seatbelt violations alone. Vehicle searches decreased dramatically after the switch to primary enforcement. Analysis of the change in number of vehicle searches revealed that Black drivers had been searched significantly more often than white drivers.

If Black drivers were found to be committing more crimes this difference might be defensible. But that wasn’t the case. In fact, the arrest rate (the proportion of vehicle searches that found criminal activity leading to arrest) was lower for Black drivers. A lower arrest rate means Black drivers weren’t committing more crime but also indicates that innocent Black drivers were more often experiencing unwarranted searches. A higher arrest rate for white drivers suggests they were only searched when criminal activity was likely, resulting in a high and accurate arrest rate. Differences in arrest rates due to unequal enforcement of laws have been observed before: “Stop and Frisk” policies are now widely recognized to have been used to profile and target racial minorities.

Unequal enforcement of any law is racist. But unwarranted stops and searches are also unconstitutional. The Fourth Amendment clearly states that individuals cannot be stopped and searched by police without reason. Despite evidence of unwarranted traffic stops and vehicle searches for Black drivers, court rulings continue to give police a free pass to fish for crime.

Black or white, no one denies the value of wearing a seat belt in ensuring passenger safety. Today, 90% of drivers and passengers buckle up, meaning that further health gains from stricter laws are unlikely. Even with high rates of seat belt usage, Alabama, Louisiana, Maine, and Washington all enacted stricter seat belt laws in 2019 in an effort to further reduce traffic fatalities. For Black drivers, the more imminent threat may be the profound physical and mental health risk of police interaction.

Photo via Getty Images