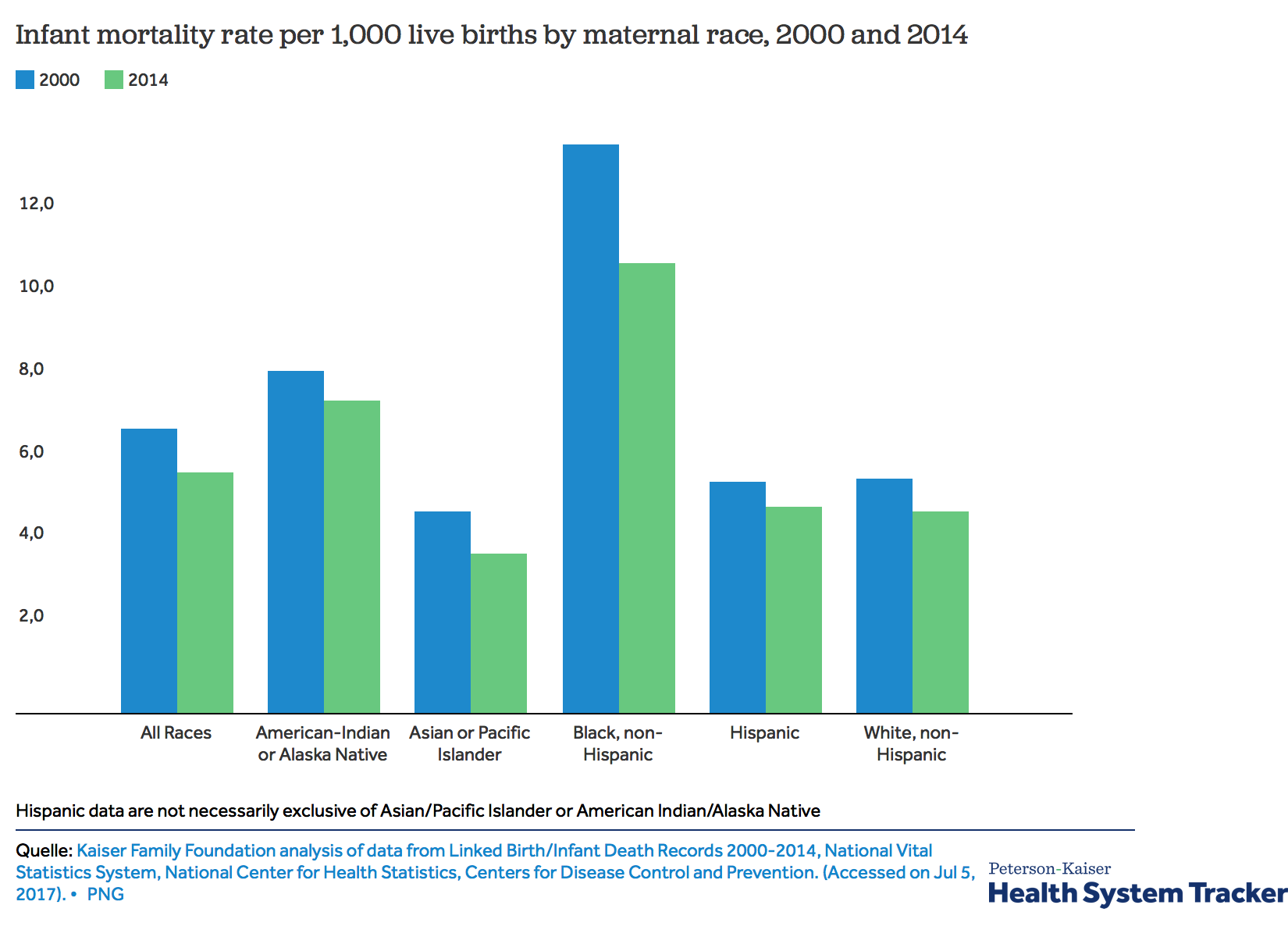

64,876 babies. That is how many Dr. Joedrecka Brown Speights and colleagues estimated could have been saved between 1999 and 2013 if the Black-White infant mortality gap did not exist. That translates to saving 12 babies a day. Dr. Speights’ recent article in the American Journal of Public Health examines the Black-White infant mortality gap in 35 states.

The infant mortality rate (IMR) has steadily declined over the past century in the U.S. Despite the decrease, the disparity between Black and White IMR persists and even grows. In 2013, the infant mortality rate for Blacks was 11.1 deaths per 1,000 live births and 5.1 for whites. The Black infant mortality rate remains two to three times higher than the white IMR.

Known factors for the Black-White infant mortality gap resulted in a decrease from 4.6 to 1.9 deaths per 1,000 live births between 1983 and 2004. The rest of the gap endures and remains largely unexplained.

Medically speaking, the leading causes of Black infant deaths are complications related to prematurity, congenital abnormalities, and maternal complications. Dr. Speights and colleagues, however, set sights on the broader perspective for Black mothers from upstream to downstream factors. They acknowledge a variety of factors such as race, socioeconomic status, maternal behaviors, access to health care, nutrition, social capital, and more that could impact infant health.

State progress

Dr. Speights and colleagues found that while many states are making progress on reducing Black infant mortality, they are less successful in closing the infant mortality gap. The authors remain optimistic because they see positive trends in 18 states that could “lead to racial equality of IMR outcomes by 2050” if progress is sustained. States like Arizona, Iowa, and Massachusetts have reduced their Black infant mortality rate by more than 30%.The study found that 13 states were successful in statistically significantly reducing the Black-White infant mortality rate gap.

Dr. Speights and colleagues recognize the complexity of this disparity. This problem requires a multidimensional approach that addresses upstream and downstream factors such as structural racism, economic justice, and health care access.

Feature image: Sheila Sund, Baby shoes, used under CC BY 2.0. Graph from Peterson-Kaiser Health System Tracker. Table from Joedrecka S. Brown Speights et al. “State-Level Progress in Reducing the Black–White Infant Mortality Gap, United States, 1999–2013,” American Journal of Public Health 107, no. 5 (May 1, 2017): pp. 775-782.