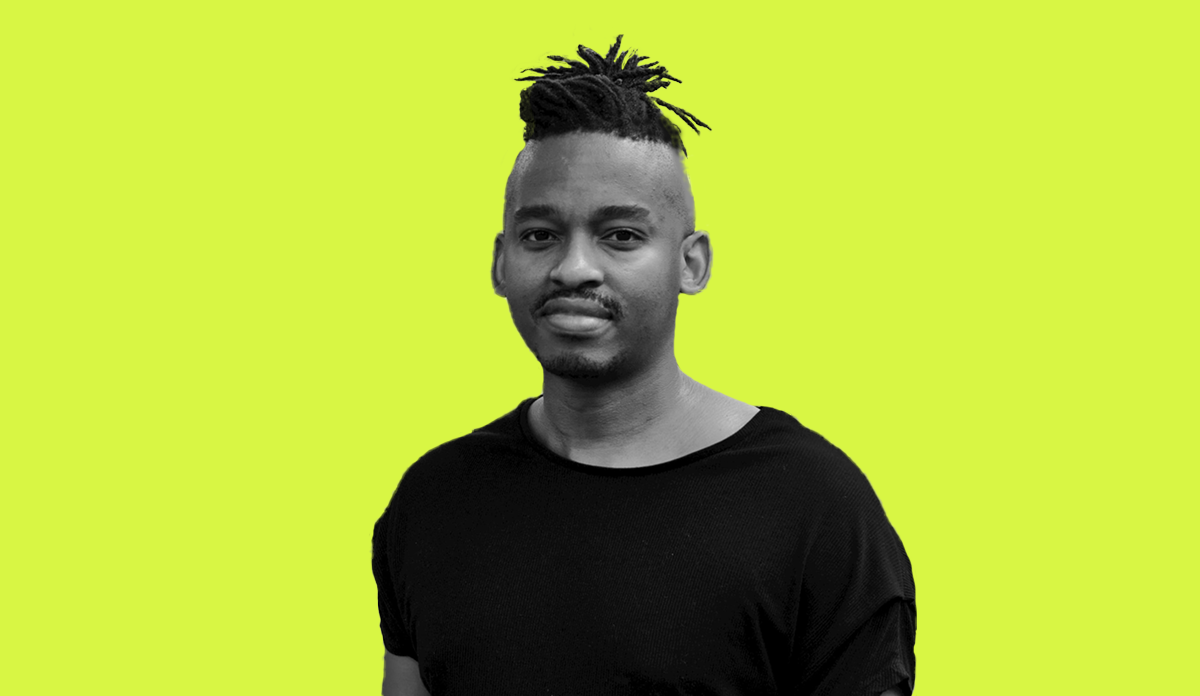

Public Health Post: Tell us about your work with the MPX NYC study. The research has not been published yet, but what other work has your team been working on to improve community response to MPOX?

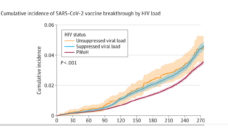

Keletso Makofane: As we saw with COVID-19, I think it’s been clear from the start that specific subgroups of people had a higher burden of MPOX and lower access to services. Black queer men are much more likely to show up as cases and are less likely to get vaccinated against MPOX. The whole point of our study was that we knew there wouldn’t be enough vaccines for everyone, and we wanted to assess where vaccines would have the highest impact.

In addition, by gathering a bunch of queer people in a weekly call to talk about MPOX, the research study group quickly became a forum where different people could collaborate and intervene. From making materials to communicate about safer sex to writing policy briefs that have already shaped public health agencies. A subgroup of us wrote guidance that was a bit cheeky and explicitly about sex because public health agencies have limitations in their language and understanding of queer sex. We’ve gotten to speak with the CDC about what aspects of our suggested delivery of services could be adopted.

We’ve seen that MPOX cases are on the decline. Is it still something that we, in particular the queer community, should be focusing on?

Even if MPOX is on the decline, people like me still need an intervention. Black queer men are more likely to show up as cases in the data collected by public health systems and also have been less likely to get vaccinated against monkeypox.

It’s another test case for our public health response. Even if MPOX is on the decline, we will have another infectious disease in the future.

MPOX is primarily occurring in groups that have experienced stigma from public health responses in the past–Black men, men who have sex with men. What can we do to prevent discrimination and stigma when engaging these high-risk communities?

To deal with stigma, as with HIV, it’s essential to use the intelligence of the people most affected by the disease. Doing this might look like having funding available for the quick formation of groups that can dedicate time and energy to a new condition while communicating about it within the community currently affected. There’s a reason people who worked on HIV response have been at the forefront of working on MPOX. HIV has given us many templates to use in response to a disease affecting disenfranchised people.

Would you describe the public health response to MPOX in the U.S. as a success?

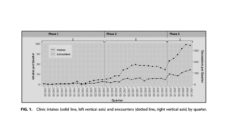

As I said, there are plenty of templates to choose from, given the international response to HIV over the past decades. The problem for people in the U.S. was that these templates are often from African countries, and the U.S. has a problem learning from experience in other countries. For example, in Kenya, community-based organizations exist across sex workers, people who use drugs, men who have sex with men, or transgender people. Kenyans organized to ensure the policies included these people. We have not had that mechanism in the U.S.–or we rebuild it every time there’s an outbreak. We had to do that at MPX NYC in 2022, and it took too long. That’s a failure. When MPOX numbers declined, supports like mobile vaccine clinics were quickly dismantled here in New York. That’s another failure. I think now we really need to understand these failures and why they keep happening.

Photo provided