“All hell broke loose, and I did not expect it at all,” says Katherine Flegal as she recalls the findings from her award-winning, co-authored paper published in 2005.

Flegal worked as a senior scientist at the CDC for almost 30 years and was one of the first epidemiologists to notice Americans were getting bigger. But when she found that “overweight” people might be healthier than people with a “normal” weight, it was the first shot fired in what is now known as the “obesity wars.”

Flegal’s research came out shortly after Ali H. Mokdad, et. al. reported obesity would soon surpass smoking as the leading cause of death. When her “counterintuitive” results appeared in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), several faculty and alumni from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health immediately started claiming the study was faulty. Critics went as far as contacting Flegal’s employer to discredit her research integrity and initiating press reports to publicly insult the findings.

Flegal has published personal accounts of her tumultuous experience trying to report data on health trends. Another article discusses the trials of being a female researcher, which likely contributed to the study’s negative reception.

Why were these public health professionals so upset? “They thought the message was bad,” says Flegal. “They didn’t like the idea that being overweight might not be associated with higher mortality, but in fact, was associated with lower mortality than being a normal weight.”

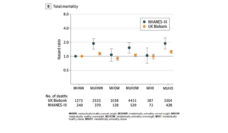

Flegal and her co-authors used more recent data than was presented in Mokdad’s publication. Trying to dig deeper into her findings, a review of 97 studies in a 2013 meta-analysis yielded the same results. Even though Flegal’s original article came out almost 20 years ago, and other research has found similar conclusions, recent articles discussing how being “overweight” might not be bad for you are still reported as surprising news.

Other studies do find being overweight increases the risk of poor health, but the many conflicting results illustrate the uncertain relationship between body mass index (BMI) and health. The BMI remains a fixture in doctors’ practices, but was originally intended to measure trends at a population level.

“I can’t think of any reason why BMI would be considered an accurate measure of individual health. People talk about it as a screening device, but screening for what?” asks Flegal. “If you want to screen for blood pressure, for example, you don’t look at someone’s BMI, you measure their blood pressure. It’s hard to see that BMI is helping anything.”

When discussing whether the upward trends in BMI over the past decades are unique to the U.S., Flegal responds, “No, they went up everywhere, which is kind of weird too. It’s not just the U.S., so there’s something else that is going on. Is it a really bad thing? I don’t really know.” Other research has criticized the accuracy of the BMI to measure individual body fat, especially as a one-size-fits-all measurement tool across populations.

The underpinnings of anti-fat bias in society, science, and research made “inconvenient findings” like Flegal’s impossible for some to accept. Flegal’s contributions have helped uncover the problematic use of the BMI, and the unresolved health effects of being “overweight.”

Photo provided