In 1962, pediatrician, Henry Kempe, published the landmark article, “The Battered-Child Syndrome,” in the Journal of the American Medical Association. Kempe was the first to characterize child abuse as a clinical condition and to spur government action on the protection of children’s rights. Later that same year, Congress passed amendments to the Social Security Act that established Child Protection Services (CPS) and a larger emphasis on child welfare. Reporting laws followed soon after. Decades later the system remains flawed. To people who have never come into contact with CPS, the prevalence and impact is unknown and ignored.

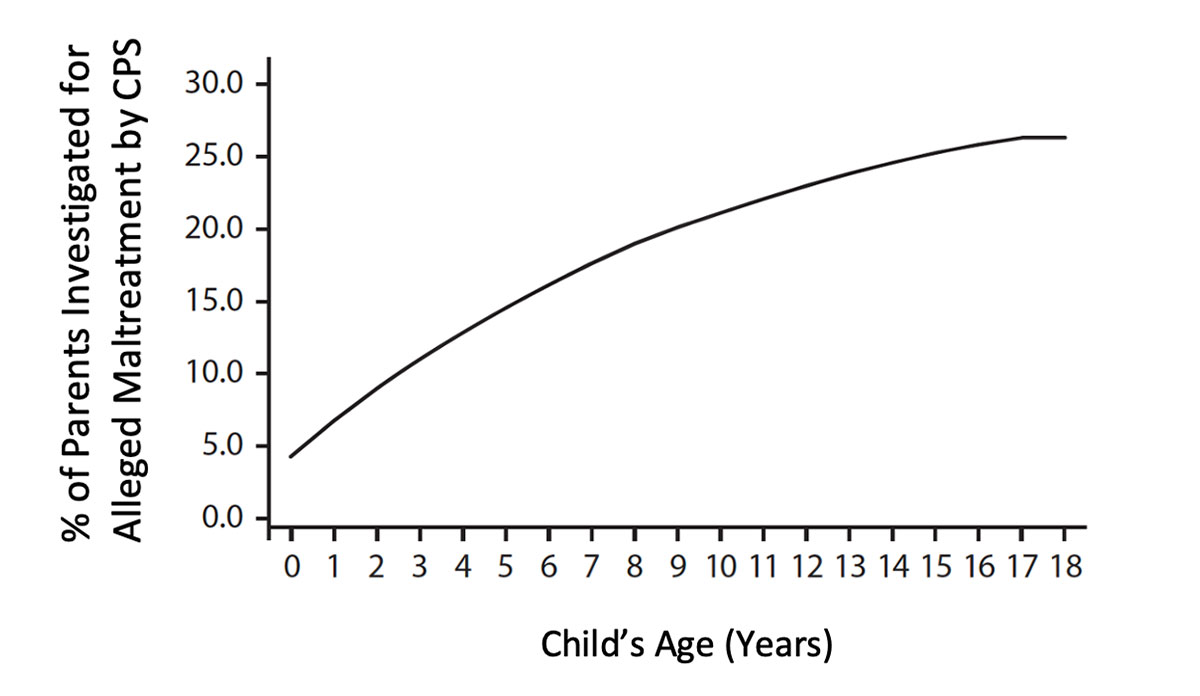

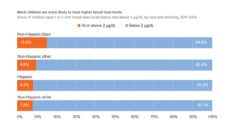

Emily Putnam-Hornstein and team used census and child protection data from California to look at children’s interactions with CPS from 1999 to 2017. The graph above shows that 26.3% of families were investigated for alleged maltreatment, representing 1 in 4 families in California. Furthermore, of the 26.3%, 10.5% were substantiated as victims of abuse or neglect, 4.3% were placed into foster care, and 1.1% of their legal caregivers had parental rights terminated. Half of Black and American Indian children’s family situations were investigated for maltreatment. Black and American Indian families also experienced involvement with CPS at twice the rates of white children.

Of course, not all abuse cases are identified and most data comes from CPS itself, potentially underestimating abuse prevalence. In fact, it is estimated that 1 in 7 children are abused or neglected annually. This number is higher than the 10.5% identified by CPS in California.

The high number of investigations harms innocent families. Investigations cause stress, can take months, disrupt daily life, and can remove children from their caregiver’s care. In addition, mandatory reporting laws increase the number of reports reaching CPS leading to an overburdened system where the majority of cases are released without cause.

Many families investigated for child abuse and neglect show signs of instability and often involve one-parent households that have low social support, and trouble affording basic necessities. Linking poverty and child services is not new. Evidence suggests that addressing poverty directly by providing families with resources to cover basic needs, such as policies like universal basic income, can be effective in reducing child abuse and neglect rates.

Cumulative Rates of Child Protection Involvement and Terminations of Parental Rights in a California Birth Cohort, 1999–2017. American Journal of Public Health, 2021.