You’ve probably heard a version of this phrase, “where you live determines how long you live.” Researchers have shown that our neighborhoods – the places where we live, work, and play – are a stronger predictor of our life expectancy than our genes. In fact, in many U.S. cities, life expectancy between communities that are a few miles away can have differences as large as 30 years. For example, in Boston, life expectancy within a 3-mile radius, drops from 92 in Back Bay to less than 59 in Roxbury. This means that a child born today in Roxbury is expected on average to live thirty fewer years than a child born in Back Bay. That is unacceptable.

These neighborhood disparities in life expectancy are strongly associated with race and ethnicity. The residents in Roxbury come from predominantly minoritized groups, consisting of 50.3% Blacks and 30.7% Hispanic, while Back Bay is 73.4% White. Structural racism manifested through policies such as redlining discouraged investments in neighborhoods with predominantly Black and other minoritized residents and produced general disadvantage. These neighborhoods tend to be poorer, have substandard housing, and fewer residents with a college degree.

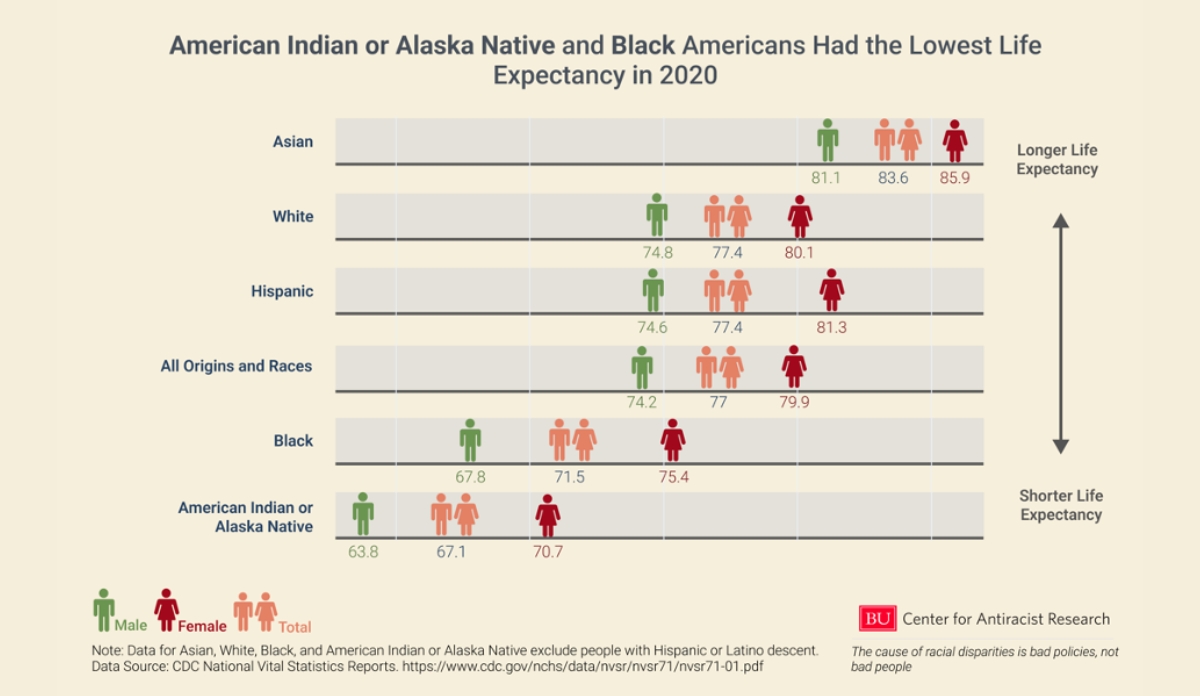

The differences in life expectancy between racial and ethnic groups worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although there was an overall drop in life expectancy across all racial groups in the U.S., the drop was most significant for Indigenous and Black people. According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Indigenous males had the lowest life expectancy at 63 years in 2020 compared to 81 years for Asian males — an 18-year difference. Similarly, life expectancy for Black males was 67 years; 7 years lower than the average life expectancy for males across all groups.

Addressing these disparities in life expectancy requires a collection of policies and interventions that target the root causes — the factors that shape where we live, work and play. For example, housing quality is a major contributor to health, and homeownership is a primary way that Americans have built and transferred generational wealth. To address disparities in homeownership, we must eliminate racial bias in home appraisals, deal with disparities in mortgage costs and access, provide down payment assistance to individuals affected by unfair loan and housing policies, among others.

Databyte via the Boston University Center for Antiracist Research. Infographic created by Yukun Yang.

Public Health Post is collaborating with researchers at the Center for Antiracist Research Racial Data Tracker to produce a series of articles focused on structural racism and health. This is the fourth article in the series. Sign up to receive our weekly newsletter to receive our latest articles.

The goal of the Racial Data Tracker is to collect, analyze, and publicly share data on racial inequities and disparities with communities and individuals interested in using racial data for research, advocacy, education and policy. The data will be available through downloadable data tables, infographics, and interactive visualizations. The project will publicly launch in Spring 2023.