Supervised injection facilities (SIFs) are increasingly being discussed in the United States as a way to reduce overdose deaths in the opioid epidemic. Here’s the final article in our week-long debate on SIFs as a harm reduction strategy. Read articles one, two, three, and four here.

Moralism is often the enemy of public health. “Moralism” is not the same as morality. By moralism I mean the practice of judging other’s behaviors based on one’s own values for determining right and wrong. Merriam Webster’s Dictionary lists “prudishness” “puritanism” and “nice-nellyism” as synonyms for moralism. Synonyms for “morality are “decency, goodness, honesty and integrity.”

There are many examples of moralism undermining public health. In World War I Army officials debated whether or not to provide their young, often naïve troops with condoms before being sent to fight in Europe. The Army decided against providing condoms because, after all, sex with someone other than one’s wife was wrong and the troops simply should not do it! Providing troops with condoms was viewed as officially condoning or contributing to immoral behavior. The predictable result of this moralistic decision was an epidemic of sexually transmitted diseases among the troops.

A more recent example of moralism undermining public health was the debate over needle exchange programs proposed to reduce the risk of HIV transmission among intravenous drug users. Relatively early in the HIV epidemic it became clear that infected needles were causing an epidemic of HIV in the IV drug using community. Because syringes could not be purchased without a prescription, and unauthorized possession of a syringe was a felony, clean needles were not available to IV drug users; needle exchange programs were proposed so IV drug users could obtain clean needles.

A more recent example of moralism undermining public health was the debate over needle exchange programs proposed to reduce the risk of HIV transmission among intravenous drug users.

While opposition was often voiced in terms of lack of evidence supporting such programs (which has since been established), the opposition, which included the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, was based on moralism. Opponents of clean needle programs argued that IV drug users should simply stop being IV drug users if they wanted to avoid HIV infection. This was expressed by saying that IV drug users should receive treatment rather than clean needles. The obvious flaw in this reasoning was that there was a scarcity of treatment beds for IV drug users who wished to receive treatment, a substantial number of IV drug users were not prepared to seek treatment, and there were IV drug users who had received treatment but relapsed.

Furthermore, the needle exchange opponents’ arguments did not demonstrate any concern for the health of current IV drug users. The “rehab only” side was essentially an “abstinence only” position, a variation of Nancy Reagan’s “just say no” approach to drugs. Advocates for needle exchange agreed that it would be better for IV drug users to stop injecting illegal, addictive drugs but accepted the fact that there would continue be IV drug users at serious risk for contracting HIV. Given this reality, proponents argued it was better for IV drug users to have the opportunity to take measures to save their lives while they continued to be IV drug users. The moralism over IV drug use slowed down the acceptance of needle exchange programs and led to avoidable deaths.

The debate over supervised injection facilities involves many of the moralistic issues that were found during the World War I condom decision and the needle exchange debate. Doesn’t providing IV drug users with a safer place to engage in their undesirable actions condone and enable their undesirable behavior?

It is notable that there have been no moralistic objections to providing EMTs, firefighters and police officers and other first responders with naloxone to treat opiate users when they suffered a life-threatening overdose at some random location. Naloxone is not treatment that reduces IV drug use. Is there a moral or policy difference between the emergency administration of naloxone by emergency responders who rely on luck and happenstance to find and treat a person who has overdosed, and providing opiate users with a sheltered place where naloxone and health providers are predictably available to save their lives if they overdose?

Providing naloxone to a drug user who overdoses is controlled by the ethics of rescue. The ethics of rescue requires immediate responses necessary to protect human life.

Providing naloxone to a drug user who overdoses is controlled by the ethics of rescue. The ethics of rescue requires immediate responses necessary to protect human life. No questions are asked; rescue is more of a reflex than a considered action. The ethics of rescue do not and cannot embrace moralism, if for no other reason than that there’s no time for it. Further, first responders cannot be viewed as condoning or enabling any behavior since they are not present when the overdose event occurred.

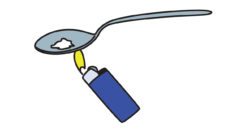

Supervised injection facilities (SIFs) are not governed by rescue ethics. In all likelihood, most SIF users will “get high” and go on their way rather than needing any treatment at all. Opiate users will use supervised injection facilities hoping they will not need naloxone, but comforted by the fact that if they overdose, their survival will not be determined by happenstance.

But isn’t it simply wrong to provide opiate users with a safer place to use their opiates? Doesn’t the creation of SIFs condone or even enable and this undesirable behavior? This is the same question that was asked about providing condoms to troops and clean needles to IV drug users. And the answer is the same—such programs neither condone or encourage undesirable activities, but accept the reality of the existence of people who engage in these “immoral” behaviors that place them at-risk for negative health outcomes. The reality is that troops had sex when they went to Europe, IV drug users shared dirty needles when clean ones were not available, and IV drug users inject potentially deadly drugs in the absence of SIFs. None of these “immoral” people needed encouragement from any government program trying to make their lives safer.

What would be immoral is to deprive opiate users who wish to take preventive measures, a core of a public health value, the opportunity to have access to these programs.

As with needle exchange programs, the opiate users who choose to use SIFs are those who understand the risks of IV drug use and care enough about their lives to go to the inconvenience of using these programs. What would be immoral is to deprive opiate users who wish to take preventive measures, a core of a public health value, the opportunity to have access to these programs. The very fact that there are drug addicts who use preventive programs such as needle exchange and SIFs challenges the stigmatizing belief that opiate users are all unthinking, uncaring and purely self-destructive individuals. Any destigmatization of this population is a positive outcome.

I have presented two examples of policies based on moralism about personal behaviors that led to a failure to reduce the risks inherent in behaviors many policymakers thought to be immoral or wrong. We should not add opposition to SIFs to that list.

Feature image: Prepping a rig, Insite, the first legal supervised injection site in North America. Photo courtesy Vancouver Coastal Health.